Show Summary

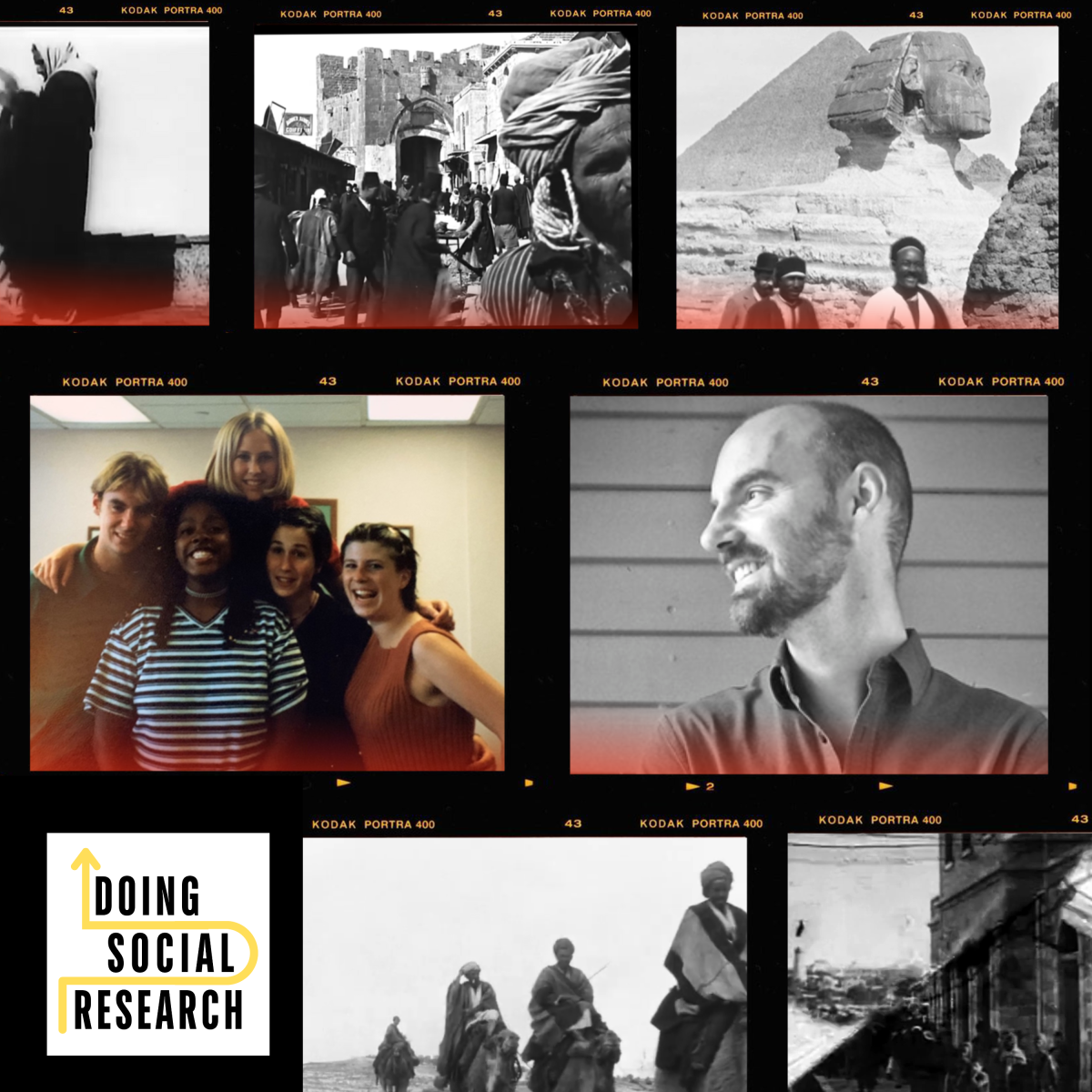

In this episode, Phyllis digs into what we can learn from error (our own and others) with the brilliant Dr. Michael Allan, a comparative literature professor at the University of Oregon. They kick things off with Mike’s latest research on late-19th-century filmmaker Alexandre Promio of the Lumière Brothers, unpacking what it means to “research an ellipsis.” They connect this film analysis to discuss the purpose of university education and how a classroom differs from a YouTube channel. Spoiler alert: contrary to the beliefs of university administrators & neo-liberal hacks everywhere, we see inefficient, emotional, and otherwise messy university classrooms as an antidote to the imminent rise of AI robot overlords. Stick around for the grand finale: Mike’s insider tips on getting published in academic journals, based on his hard-won wisdom from his years as editor of the oldest journal in his field, Comparative Literature.

Guest Bio

Dr. Michael Allan is an associate professor of Comparative Literature at the University of Oregon, where he is also affiliated with the Cinema Studies Program; Comics and Cartoon Studies; and Middle East and North African Studies. He is the author of In the Shadow of World Literature: Sites of Reading in Colonial Egypt, published with Princeton University Press in 2016 and co-Winner of the MLA Prize for a First Book. He is editor of Comparative Politics, and has also guest edited a special issue of Comparative Literature, an issue of Philological Encounters with Elisabetta Benigni, and a dossier with Bruno Reinhardt devoted to the work of Saba Mahmood along with numerous other articles and book chapters.

Before joining the University of Oregon, Dr. Allan was a member of the Society of Fellows in the Humanities at Columbia University after earning his Ph.D. from the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley, under the direction of Karl Britto and Judith Butler.

Works Cited

Allan, Michael. 2016. In the Shadow of World Literature: Sites of Reading in Colonial Egypt. Princeton University Press.

Allan, Michael, and Bruno Reinhardt. 2019. “Pensando Com Saba Mahmood: Apresentação.” Debates Do NER 2(36):137.

Arendt, Hannah. 2018. The Human Condition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Buber, Martin. 2010. I and Thou. Mansfield Centre, CT: Martino Publishing.

Promio, Alexandre, dir. 1896. Prière Du Muezzin.

Promio, Alexandre, dir. 1897. Porte de Jaffa: Côté Est.

People Mentioned

Louis Althusser

Emile Benveniste

Ivy Bourgeault

Karl Britto

Judith Butler

Eugène Delacroix

Mary-Anne Doane

Tyler Escott

Anton Kaes

Chloe Kim

Saba Mahmood

Trinh T. Minh-Ha

Devon Powers

Kaja Silverman

Learn More About

- How to read social science research

- Phyllis’s formula for an introduction

- An outline for social science research papers

- A checklist for good writing

Corrections

At least according to Forbes Quotes online, Michael Jordan said: “I’ve missed more than 9,000 shots in my career. I’ve lost almost 300 games. Twenty-six times I’ve been trusted to take the game-winning shot and missed. I’ve failed over and over and over again in my life. And that is why I succeed.”

Transcript

(a barely edited, transcript produced with MS Word’s Transcribe tool)

Hello and welcome to doing Social Research where I talk with some of my favorite people who do Social Research to dig into the cool projects they’re working on, along with the struggles and successes they’ve had in their careers. My goal is to help demystify research for students, help other researchers hear stories of others wins and losses and provide a platform for all the brilliant work of folks doing research in the humanities and social sciences.

I’m your host, Phyllis Rippey, a professor of sociology at the University of Ottawa and creator of the website doingsocialresearch.com. I’ve been teaching research methods for over 15 years and have carried out my own sociological research using both qualitative methods and advanced statistics.

But today we’re not here to talk about me. We’re here to talk with my dear friend, he amazingly brilliant, award-winning doctor Michael Allen (feels weird to call you, Michael, but I feel like I have to start with Michael because it’s, you know, your name), associate professor of comparative literature at the University of Oregon, where he is also affiliated with the Cinema Studies Program, comics and cartoon studies and Middle East and North African Studies. Mike Mike holds a PhD from the Department of Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley, where he worked under the direction of Karl Britto and Judith Butler.

Which he followed in 2008-2009, as a member of the Society of Fellows and the Humanities at Columbia University. His research focuses on debates and world literature, post colonial studies, media theory and film and visual culture, primarily in Africa and the Middle East. In both his research and teaching, he bridges textual analysis with social theory and draws from methods and anthropology, religion, queer theory and area studies.

He’s the author of In the Shadow of World Literature: Sites of Reading in Colonial Egypt, that was published with Princeton University Press in 2016 and was a co-winner of the MLA Prize for first book. And what Mike fails to mention in his bio that I just totally plagiarized from his University of Oregon website that he was also a summer intern at a certain feminist organization that I don’t know, maybe we won’t name, in Washington, DC, during the summer of 1997, where we became lifelong friends and his research portfolio was way ahead of its time because he was looking at the feminist pop culture icon Barbie.

So I am so excited to talk to you. Aside from all of your jaw-dropping like brilliance, you’re just one of my favorite people in the world that I keep telling you. And you’re my favorite man on Earth, which includes my husband and no offence, but he probably won’t even listen to this. So anyway, welcome. Welcome, welcome. I’m so excited. You’re here!

00:02:35 Speaker 2

Thank you for this so much. I’m already it’s it’s a delight to be here and and just great to get to chat with you in this.

00:02:41 Speaker 1

Totally. I have so many. I have so many questions and so many things and.

00:02:45 Speaker 1

I just want to know about everything, but because I’m trying to like build a brand here, I like to like ask the question about doing Social Research. So like what? What’s the research that you’re doing these days?

00:02:56 Speaker 2

So I have a a couple of things going on, but the main thing I’ve been working on this past couple of years is a book that is devoted to essentially an ellipsis that exists in a travelogue.

00:03:09 Speaker 2

And so I was interested dot dot dot so, you know, many scholars are interested in the impossibility of an origin story. And so I was always curious when people tell the story of film and media in the Middle East, there’s this curious company called the Linear Brothers Film Company they sent.

00:03:10 Speaker 1

Like dot dot dot ellipsis.

00:03:13 Speaker 1

Hey, yeah.

00:03:29 Speaker 2

Camera operators in 1897 across the globe among the places they stopped was in the Middle East.

00:03:37 Speaker 2

And so.

00:03:39 Speaker 2

I looked at the travelogue of one of those camera operators and curiously, he has like a brief mention that he was in the Middle East, but essentially skirts right past it and spends much more time on other things. So this entire research project is essentially leveling with the fact that there’s this ellipsis in this travelogue, but there’s an abundance of visual evidence.

00:04:00 Speaker 2

Over 90 films that he shot on those journeys, and so how we reckon with different types of evidence. Visual evidence, as opposed to discursive evidence, and so.

00:04:10 Speaker 2

That’s the. That’s the sort of the the thing that prompted me into this project initially.

00:04:15 Speaker 1

That’s like, so interesting. And I love impossible to answer questions that we somehow come up with some kind of answer for. I have all these very specific questions that might get irritating to you, but we’re going to just assume we’re going to talk to me like I’m.

00:04:31 Speaker 1

A5 year old.

00:04:31 Speaker 1

With a PhD, whatever that means.

00:04:35 Speaker 1

So OK, so the Lumière brothers were this production company and the guy was.

00:04:42 Speaker 1

Promio right, the camera operator so can who tell me more about the the film company is, are they the people who did the like the thing in the moon is that them or is that something else?

00:04:52 Speaker 2

No. So right after. So Georges Méliès. Yeah. Passes. But so they’re linear brothers often in stories of early cinema. You know, there’s the Edison Company in the United States and then in France there’s the Lumière brothers Film Company that actually started. It was primarily a company for photographic plates.

00:04:54 Speaker 1

Oh, OK.

00:05:11 Speaker 2

But at a time when a number of people were experimenting with optical devices, the Lumière brothers patented this machine. They called the cinematograph.

00:05:22 Speaker 2

And it was portable, so part of its in contrast to the Edison Company who that where there was a reliance on studio based filming, you have to have certain lighting conditions and all of these other things. The cinematograph worked as both a projector and a recording device. So I mean.

00:05:41 Speaker 1

It’s just like an iPhone.

00:05:42 Speaker 2

Yeah, exactly. I was about.

00:05:44 Speaker 2

To say camcorder, but that because that dates me a little bit.

00:05:50 Speaker 2

And so yeah, I mean.

00:05:52 Speaker 2

Are they the first? No. Did they invent cinema? No. But within the mythological account, they are among the first people to in certain in certain entrepreneurship to how they approached it. And the cinematograph was sent.

00:06:05 Speaker 2

Almost immediately, all across the world, so I say not just the Middle East, but like Russia, what was then into China, Canada, the US, Mexico, Japan ever.

00:06:10 Speaker 1

When?

00:06:18 Speaker 1

That’s so cool. So these would have been, like, very short films, right? Like, this isn’t like you have a director and you have a producer like so, like, was the camera operator also kind of the director and the like, was this someone who had a lot of agency over making decisions about what what he was taking in?

00:06:34 Speaker 2

Absolutely. And I love your question because it hits it exactly why I’m interested at this moment, which is there is, it’s what I call film before film culture. So the very conditions we have as spectators assumptions we have about what it is to look at as a look at a film don’t exist.

00:06:45

Oh.

00:06:53 Speaker 2

So even the vocabulary that the camera operator camera operators used at this moment was like animated views or maybe motion photography. So there were, you know, Magic Lantern shows there a whole set of.

00:07:08 Speaker 2

Existing.

00:07:11 Speaker 2

Structures within media culture by which to observe photography and motion, but it’s certainly even within three years what it meant to look at a film looked totally different. So it’s like one of the challenges I love is like, how do we think about a moment that’s captured?

00:07:29 Speaker 2

On camera.

00:07:31 Speaker 1

Hmm.

00:07:31 Speaker 2

Through eyes that no longer look at a camera in the same way. So I have a chapter where these photographers are coming off a boat and they’re facing the cinematograph for the first time. So what’s at stake in an encounter where you have a photographer stare at a device that’s capturing them in motion?

00:07:50 Speaker 2

And and it’s that sort of.

00:07:52 Speaker 2

Impossibility. A shift in vocabulary. A shift in frames of reference. A world that has yet to be being captured on film, that that fascinates me and.

00:08:01 Speaker 2

I I’d say.

00:08:02 Speaker 2

You know, it’s this sort of, it’s almost a fold in time that as a researcher, if if the book begins with this ellipsis, every chapter is more or less haunted.

00:08:12 Speaker 2

In constructively haunted, I would say by that question of how 1 looks at a film that isn’t.

00:08:19 Speaker 2

An object in the way it would be in.

00:08:21 Speaker 2

10 or 20 years.

00:08:22 Speaker 2

So even though to to get back to your first question about the Lumière brothers?

00:08:26 Speaker 2

Most of these camera operators quit making films because they thought no one’s going to want to stare at a rectangle on a wall.

00:08:34 Speaker 2

So film has run its towers and they moved on to X-ray photography. They had this thing called the Photorama, which was this 5m tall, 360° immersive photograph you could walk into.

00:08:36

Wow.

00:08:46 Speaker 1

Ohh like the old like stereo. What are the stereo with the horse running thing like the first one? Yeah, I remember I took a film class in 7th grade so I’m an.

00:08:49 Speaker 2

Yeah, like one of those, yeah.

00:08:55 Speaker 1

Expert.

00:08:57 Speaker 2

Yes, these are more like panoramas, so they’re they’re huge and immersive, and you walk inside.

00:09:03 Speaker 2

But yeah, all of that said that, so this is sort of paths not taken that interest me and even to call it film history is strange. I mean the intersection between film history and media theory I think are inseparable at this moment that, you know, 1896-97.

00:09:18 Speaker 1

Yeah, right, because.

00:09:21 Speaker 1

OK, because they weren’t like they weren’t films like they weren’t like, it’s just this and they’re just sort of.

00:09:27 Speaker 1

It’s like playing with clay or something like, do you call that a sculpture? Like they’re just sort of trying to experiment with what it is interesting and. And so why? Why this guy? Why? Why this camera? Cause at first too when I read like camera. Robert, I’m like I’m thinking in modern day film I’m like, well, that’s neat. It’s like you could use the grip or like some other random stagehand.

00:09:47 Speaker 1

But obviously this person it’s much.

00:09:50 Speaker 1

They’re not just holding the camera so, but why this this person?

00:09:53 Speaker 2

Right.

00:09:55 Speaker 2

Yeah. And it’s interesting. I mean, I think it’s important distinction, which is there’s a way that Alexandre Promio becomes.

00:10:03 Speaker 2

Inseparable from some of these, like he’s then name linked with these films. Whether he actually took the we don’t know, you know, so it’s there’s, you know, in as much as there’s an ellipsis. So too is there an open question about who shot these films. So what we have then is a type of visible evidence.

00:10:23 Speaker 2

With all sorts of speculation, so you don’t see the person behind the camera, but you’ll certainly see people looking at the camera.

00:10:30 Speaker 1

Hmm.

00:10:30 Speaker 2

And so it’s a set of encounters that are both aesthetic and technological that.

00:10:36 Speaker 2

Really. Truly, I find utterly fascinating.

00:10:39 Speaker 1

Yeah. I just like what? Why wouldn’t he have taken them? Like who? Who would have been the one to have been behind the camera?

00:10:47 Speaker 2

It’s unclear, so I mean one of the, I mean this is not to get too granular, but one of the things like the camera operators that was it was a mechanical was essentially a reel on the handle on the side of the sink.

00:10:58

Morning.

00:11:00 Speaker 2

Photograph and it had to be rotated at a certain pace in order to capture the image at a certain rate, and so there was a training whereby only certain people had that skill of how to shoot it at the proper rate. So it wasn’t like home video technology that was radically available.

00:11:20 Speaker 2

Everyone is like cadre of like 12 to 30 camera operators. Depending. You know who had this skill.

00:11:20 Speaker 1

Right. Like you don’t just push the button.

00:11:27 Speaker 1

OK. But so was he, like, more prolific than others? Like is he?

00:11:32 Speaker 2

Yeah. I mean, it’s funny because, I mean, his name exists, but he’s not the subject of the book. I’d say what I try and anchor are specific films. I call it a micro history of world cinema in that every chapter takes 142nd film from a particular site from this voyage. So it’s a chapter of a film on the Great Pyramids in Egypt. There’s a chapter at the Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem.

00:11:56 Speaker 2

There’s a chapter of a prayer on a rooftop in Algeria. In each film is ultimately what interests me more than Homeo, who shot it or, you know, it’s like, what? What does this make visible for us as spectators?

00:12:04 Speaker 1

OK.

00:12:09 Speaker 1

So what does it? So what’s what? Can you can it be a spoiler about your book? People buy it. Buy mikes book.

00:12:16 Speaker 1

When it comes out, this will be a teaser.

00:12:20

Yeah.

00:12:20 Speaker 2

Yeah, I mean, so I’m driven, you know, is it I’m driven by questions and to me, these films each raise a question about what it means to see. So what is made visible? I’m fascinated by those sort of unintended details that happen to appear on the screen.

00:12:41 Speaker 2

I’m not alone in that, because early film theory is obsessed with smoke or waves or all of the leaves blowing in the wind, but I think there are certain there’s one film in particular where the of the prayer it’s a fake prayer of a, you know, someone it’s supposed to be a Muslim prayer.

00:12:41 Speaker 1

And I love.

00:13:01 Speaker 1

But it was like staged.

00:13:01 Speaker 2

It’s a man rising font, totally staged, but what’s amazing is that the man’s head falls in and out of frame, so it’s misframed.

00:13:10 Speaker 2

And so that’s often read as a mistake, obviously, that it’s a question of like had the camera operator centred the subject in the frame then it wouldn’t have happened and yet there.

00:13:25 Speaker 2

It just to me, like, raises incredible questions about what it is to gesture to a world beyond the frame that we don’t assume that the man’s head is disappearing when he falls at a frame, but also just raises a question about what would in the medic representation of a prayer look like.

00:13:44 Speaker 1

What do you mean by that? Just for for I totally know what memetic means, but for people who don’t, what do you mean by a memetic representation?

00:13:48

Right.

00:13:51 Speaker 2

Let me just put it simply like.

00:13:52 Speaker 2

What would it mean to represent a prayer on film?

00:13:56 Speaker 1

Yeah.

00:13:57 Speaker 2

Poorly and the fact that you’re filming a prayer means that it’s not actually a prayer. You know that.

00:14:03 Speaker 2

It’s it’s a.

00:14:04 Speaker 2

Prayer works in, pragmatically speaking, because it’s operating within a certain ritual context. So when it’s filmed, it’s already going to be outside of that ritual context. So the fact that it’s misframed.

00:14:18 Speaker 2

Is only drawing attention to the fact that every prayer is going to be, in a sense, fabricated in misframed, even though this one is quite obviously so.

00:14:27 Speaker 1

Interesting and and that I mean, am I being too literal but like?

00:14:32 Speaker 1

Like a prayer is happening in your mind. I mean, at least for me, like I.

00:14:35 Speaker 1

Do say my prayers not.

00:14:37 Speaker 1

Like every night. But I I will pray, I say the serenity prayer with some regularity. But it you know, it’s like happening in my mind like it’s. And so the fact that his head is literally, I mean, am I being too literal here like that his head is going in and out of the.

00:14:50 Speaker 1

Frame is that in any way?

00:14:51 Speaker 2

Big question. I mean, you know the the.

00:14:53 Speaker 2

The.

00:14:54 Speaker 2

The you know this isn’t necessarily part of the book, but the assumption that prayer is an internal activity has a particular history to it that you know. But in this sense, I I don’t. You know, there’s a sense of the ritual nature of a prayer is not necessarily an internal activity. So there’s a way that the the gesture of rising and falling in prayer.

00:15:15 Speaker 2

Is the condition through which an utterance or recitation or a mode of hearing a recitation at the moment of prayer is made possible. So rather than it being an interior activity of, you know, the Protestant notion of a conversation with God.

00:15:31 Speaker 2

Instead, you have kind of a disciplining of the body to be receptive to a call to a particular, you know, active activity. I mean that this prayer is so clearly fabricated, is not it. It almost falls off the IT gets, not it.

00:15:51 Speaker 2

It it doesn’t at all serve as an index of what a prayer could be, although like Orientalist artists, Delacroix onward, like they’re obsessed with painting prayers and showing prayer in that context. So I kind of like this object is a misfit from the Orientalist archive, because it’s it’s Orientalist paintings are often.

00:16:11 Speaker 2

Of course, framed properly, it positions the spectator to have a command over the visual scene, so if a subject is framed in the centre, Hue 2 as a spectator, have a command over the scene, whereas in this film you’re decentered it doesn’t seem proper.

00:16:28 Speaker 2

So it’s often seen as like ethnographic and objectifying, but the whole point is like absolutely, it’s not because it breaks this convention. So it makes you aware of the fact that it’s misframed.

00:16:39 Speaker 1

Oh my God, that is so fascinating. Yeah, that it is the breaking. It’s in the. It’s in the breaking of of that framing. That is where something interesting happens. And I’ll just like, I just. I love this blur. Like in your book blurb that you wrote. And I’m just going to say your words back to you, cause I think they’re just so beautiful. But you you wrote.

00:16:59 Speaker 1

By attending to archival slips and reframing.

00:17:02 Speaker 1

The book offers what we might call a counter archival history of world cinema. On the one hand, it is an excavation back in time to unsettle and rework the relationship between seeing and traveling and the other. On the other hand, it is a consideration of the conditions of seeing and being seen at specific locations across the various chapters. I avoid the generalized.

00:17:22 Speaker 1

Clogging of films according to a logic of chronology, and I flipped the politics of location to attend to the slippery distribution, exhibition and appropriation of cinema. What emerges as an argument for a mode of seeing the kernel of the world in cinematic details, and of tracing the afterlife of the Lumière Archive in the hands of contemporary artists and photographers?

00:17:42 Speaker 1

And it’s like, I mean I I hear like reading that and what you were just saying, it’s sort of clear like this because it’s, yeah, this this space of what it’s like where they kind of where they ****** it up is the truth. If there is like not that there is a truth but like, that’s where the interesting.

00:18:00 Speaker 1

Things happen.

00:18:01 Speaker 2

Well, so it’s interesting. So I my training is in comparative literature. So I trained in, you know, French literature, Arabic literature, also film and visual culture.

00:18:11 Speaker 2

And yet, I’ve also trained alongside philosophers and anthropologists. And so the assumption, you know, an anthropology, you have the ethnography as a researcher, you go into the field, you observe, and are living in part of a situation. You write up your notes, you come back. And that’s your sort of the analytic space.

00:18:30 Speaker 2

In comparative literature, you have close reading. You attend to a particular aesthetic object, and in living with that text, certain questions are generated and.

00:18:41 Speaker 2

I think for me.

00:18:43 Speaker 2

I have this to come sort of full circle the.

00:18:47 Speaker 2

The Lumière films are not merely aesthetic objects that one can ponder in isolation. The anthropology and philosophy side of me has to recognize that there’s particular frames in which these films get shown and in which they come to be understood.

00:19:06 Speaker 2

So there’s not really a right or wrong reading of a Lumière film because film there is no.

00:19:15 Speaker 2

I mean it’s it’s a, it’s an an aesthetic form designed to be projected and in being projected, it’s iterated in its ephemeral. It shares somewhat in common, not with theatre in the sense of performance, but theatre in the sense of an ephemeral iteration. In the case of film, it’s like light projected on screen. So all of that to say.

00:19:36 Speaker 2

That’s why I think I have a particular obsession with engaging the common stories through which early cinema hasn’t been under.

00:19:47 Speaker 2

And then the aesthetic disruption that looking at these films differently offers troubling the myths through which we’ve come to understand early cinema. It’s that sort of push me pull you effective.

00:19:57 Speaker 1

So.

00:19:59 Speaker 1

Yeah. So, So what are the myths of early cinema?

00:20:04 Speaker 2

Yeah. So I mean, there’s a a common story which is, you know, that early cinema, you know, arises in France and the United States, and each country has its own history. But there’s a A parallel history in Germany and in the UK.

00:20:19 Speaker 2

And that these films, shot in the Middle East are somehow in Imperial lens. They’re not native to the territory, so they’re taken in, blah blah, blah. And and I think that’s a very important and absolutely crucial understanding, which is like the there is a kind of racist.

00:20:37 Speaker 2

Ethnographic frame colonialist history to the projectory trajectories and the way these films.

00:20:44 Speaker 2

Observe and what they lend, but that that story that’s been told relies on the fact that these films would be shown to European audiences. And yes, they were. But they were also screened in the Middle East, and so, and even among European audiences, different spectators might have different relationships to the places that are being depicted.

00:21:04 Speaker 2

And so part of the project is interested in contemporary artists and film makers.

00:21:09 Speaker 2

From the Middle East, who take up this early Lumière archive and iterate it differently, they you know, it gets pulled in different directions. And So what I don’t want to do is tell a story of the Lumière brothers that sticks it on a board like an insect and a collection to go die and stand on a screen somewhere.

00:21:29 Speaker 2

Can be shoved in a drawer. Part of my interest is in the the potential history that every single one of these films has. That’s to say I’m not. I’m not interested in telling you a story of what it means, and this is how it ought to be understood.

00:21:43 Speaker 2

That but of saying, well, look at the afterlife that this particular image has when it’s framed this way or understood this way or brought into relation with this, this other text, that’s not to sound too obtuse in saying all of that.

00:21:53 Speaker 1

Can you give us another?

00:21:57 Speaker 1

So I find it fascinating. Can you give us one another example to illustrate what you’re talking about?

00:22:02 Speaker 2

Yes. So if if I first mentioned the film of the prayer in Algeria, another film that’s, you know.

00:22:09 Speaker 2

Struck me over the years. This is a film of the Jaffa Gate in Jerusalem, and it’s one of these very conventional St. scenes. So this cinematograph was often brought onto the street, set up on a tripod. The camera operator would record people passing in front of the camera. And so the setup here, the camera.

00:22:28 Speaker 2

Shoots.

00:22:30 Speaker 2

On, you know, through a passageway at the Jaffa Gate and you see a number of pedestrians walking by. Of the number of pedestrians, one of the pedestrians comes very close.

00:22:40 Speaker 2

To the camera.

00:22:41 Speaker 2

Crosses in front of it and then crosses back across, and then crosses again across, cutting out the image behind it. So all you see is this huge face.

00:22:50 Speaker 1

It’s like a 19th century photo bombing.

00:22:53 Speaker 2

That’s amazing. We have understanding it. I mean it. Yeah. I guess what a photobombing might be in the background and what’s amazing is that this comes into the foreground. So you essentially have a face that eclipses the landscape.

00:23:06 Speaker 1

Ah, so it’s.

00:23:06 Speaker 2

Because the face becomes it’s all face for for just a brief instant.

00:23:07 Speaker 1

Like all.

00:23:12 Speaker 2

But it’s also a face that interrupts. How?

00:23:16 Speaker 2

That gets a face that is essentially coming so close up to the camera that you lose a sense of depth and perspective that you had when you were looking at the landscape.

00:23:26 Speaker 1

How unsettling.

00:23:27 Speaker 2

As the face is kind of flat and so the face becomes a screen and it’s a spectator, you’re staring at eyes that are looking back at you. But those eyes were filmed in 1897, and you’re watching it, whatever 2024.

00:23:43 Speaker 2

And so.

00:23:46 Speaker 2

One of the commanders, for me there is like what is it to think about this close up or a face in world cinema is what is it to read us an understanding of where this film takes place, when it’s radically particularized in the eyes of that particular pedestrian?

00:24:05 Speaker 2

So a social scientist would be like, wow, this is amazing. It’s like a photograph of the Jaffa great in 1897. Look what people are wearing.

00:24:14 Speaker 2

Look how they’ve walked like.

00:24:14 Speaker 1

This is where my brain is going, yeah.

00:24:17 Speaker 2

You have you. You have.

00:24:19 Speaker 2

Muslims, Jews, Christians, all strolling up the street and you understand that because of how they’re dressed and blah, blah, blah blah blah.

00:24:26 Speaker 2

That’s great. And I I’m invested in.

00:24:28 Speaker 2

That way of thinking, but the.

00:24:30 Speaker 2

Formal questions. So for the social scientist, you look at the scene and say it reveals the social world because it captures it at the.

00:24:39 Speaker 2

Moment.

00:24:40 Speaker 1

Yeah, yeah.

00:24:40 Speaker 2

And the media theory side of me is.

00:24:42 Speaker 2

Like, well, wait a minute.

00:24:42 Speaker 1

Yeah. Tell me.

00:24:45 Speaker 2

It’s not just that you see a world through the camera, but the camera is making the world visible in an entirely new way. And what is it to see the face eclipse a landscape that’s not only a question of wow, look what that guy’s wearing.

00:25:01 Speaker 2

It’s a question that draws attention to the act of filming itself, because essentially what’s happening is this pedestrian interrupts the camera operator, and at the moment of interruption, the ethnographic scene.

00:25:15 Speaker 2

Where one has a visual command over all of the pedestrians is unsettled.

00:25:20 Speaker 2

And so there again, like the classic reading, this is ethnographic. This is colonialist is turned on its head through a formal accident.

00:25:27 Speaker 1

Yeah.

00:25:27 Speaker 2

A guy who happens to approach the camera in a way that no other pedestrian really had up to that point.

00:25:35 Speaker 1

And that he’s suddenly taking control.

00:25:38 Speaker 1

Like he’s now in charge of the filming.

00:25:41 Speaker 2

Truly eclipsing the scene.

00:25:43 Speaker 1

Yeah, that is. So that’s so interesting. So you you have these three chapters that are like the 342nd films, right?

00:25:53 Speaker 2

It’s actually it’s 7 chapters and each one is anchored around like one film. Yeah. So it’s like all these microscopic snapshots.

00:25:56 Speaker 1

Oh OK so 7.

00:26:02 Speaker 2

That engage that broader question of a social world versus an not versus but an aesthetic world in a social world. And how do we think those two together?

00:26:10 Speaker 1

Yeah. And what kind of a? I mean, do you do you have a conclusion that you draw like what is sort of what is what’s your point, Mike, what’s your point?

00:26:21 Speaker 2

That’s great. It’s funny because when you first asked him, like, well, this is the question that the book is engaging and this is it. And I would, well, I’ll answer your question a little more directly by saying I arrived at this project as a scholar interested in world literature for my first.

00:26:40 Speaker 2

Book.

00:26:41

MHM.

00:26:41 Speaker 2

In World cinema for the second book.

00:26:44 Speaker 2

And so why a microhistory of world cinema? And it’s precisely the point that we’ve been returning to a little bit in the last few minutes, which is that the world as social world and the world as aesthetic world are brought to bear in the image in a way that means, as scholars of the image.

00:27:04 Speaker 2

Looking at frames, looking at formal dimensions avails us in a you know, a new way deep familiarizes the world we thought we.

00:27:11 Speaker 2

Knew.

00:27:12 Speaker 2

And it’s a defamiliarization that’s not turning on the orientalist cliche of oh, I’m seeing other nests on the camera because the other nest isn’t what you’re seeing through the camera. The otherness is the camera.

00:27:24 Speaker 2

For every single person facing the camera in 1897, that machine is a stranger. It’s no more indigenous to France than it is to Egypt, or, you know, Palestine or Algeria. And so how do we think?

00:27:39 Speaker 2

Technological, aesthetic otherness rather than simply, and to me, if we think that, then we really do kind of unsettle some of the conventions of.

00:27:49 Speaker 2

You know, I see a, you know, I see a Canadian on film or oh, I see a fill in the blank of whatever legal, political, social category you think you observe.

00:27:53 Speaker 1

Right.

00:28:00 Speaker 2

Even in and just not to belabor the point, but even in cataloguing these films, you know they were shot during the Ottoman Empire, but they were archived after the Ottoman Empire. So place names.

00:28:14 Speaker 2

Istanbul, Constantinople, Turkey, Ottoman Palestine versus Israel versus Palestine. Algeria was a colony so that the social history has moved.

00:28:27 Speaker 2

And the categories for archiving them have.

00:28:29 Speaker 2

Likewise shifted as a result.

00:28:31 Speaker 2

So that’s just another very concrete way of saying these worlds are these films are always out of sync with the world that tries to understand them.

00:28:40 Speaker 1

Interesting. It’s so Butler ish.

00:28:47 Speaker 2

Maybe we never, never escape those who train us.

00:28:51 Speaker 1

Well, I was. I had lunch with Chloe Kim, who’s on a previous episode and also my colleague, Ivy Bourgeault, who I just did an episode with. And one of the things like both of them were talking about was sort of disruptions and the ways in which, like, for so many people, that kind of idea of seeing the world in a new way.

00:29:12 Speaker 1

And be very scary. Or it could be, you know, and it can lead people to be very violent. And I think it’s like.

00:29:18 Speaker 1

There’s something you know, and I think Butler because I know her work more than not that I’m an expert, but more than like film theory is, you know, the sort of this idea like.

00:29:30 Speaker 1

There are people who are very unsettled, I think by some of the ideas she’s put out there because it does sort of question how things that we take for granted, which is also a sociologist.

00:29:42 Speaker 1

What I think is what I love about sociology is where we can sort of like turn reality on its head and sort of question and challenge these just these assumptions that we make that feel so natural that feel just like, well, obviously we have to like, you know, like, well, my work is always about breastfeeding. It’s like well, obviously breast is breast.

00:30:03 Speaker 1

Natural is good whatever, whereas it’s like, well, actually it’s a lot more complicated than that. And there’s something like really evocative about what you’re talking about in your work, where it’s like.

00:30:13 Speaker 1

These like like literal visual disruptions that are seem so inconsequential. And yet if we actually pay attention to those fissures to those errors, mistakes, ellipses that there’s a lot to conceptualize, there’s just something very cool about these, sort of.

00:30:33 Speaker 1

And something I really like about Butler or, you know, sort of post structuralist thinking or or things that I wasn’t super trained in, but I’m just like.

00:30:43 Speaker 1

It there is something. If you let yourself. It’s like being on a roller coaster. You can either like grip really tight or you can just like, let go a little bit and relax and be like it’s OK. Things can change. You can think of things in a different way and and trust that like the ride will end. But like, let’s, maybe we’ll get some maybe roller coasters bad because it’s so circular, but.

00:31:03 Speaker 1

You know what?

00:31:04 Speaker 1

I’m saying, does that mean that makes sense?

00:31:05 Speaker 2

No, it’s interesting to hear. I mean the the genesis of this project actually came from a film professor. I had Anton Kaes, Tony Kaes, who was teaching a course on film historiography.

00:31:16 Speaker 2

And gave a challenge in the class to say I’ve never and it was kind of a joke, but he’s like, would anyone think about writing an entire seminar paper on one Lumière Brothers film?

00:31:27 Speaker 2

And everything, it was just kind of wasn’t meant as, oh, someone and I. That was where this project started, which was.

00:31:33 Speaker 1

You’re like **** that. I’m gonna write it. ****.

00:31:35 Speaker 2

I’m going to do it. Yeah. And so that’s basically what happened. But I think that that type of attention, I mean, Judith Butler, you know, they were a student of pulled him on at Yale and then part of that moment of, you know, close reading and incredibly attentive.

00:31:54 Speaker 2

Attention to particular details, often like a capacity to look at a poem and sort of take it.

00:32:00 Speaker 2

Into part and.

00:32:01 Speaker 2

And it’s that that I think has, you know, if I see a legacy of something where that I was taught or trained in it was how to understand the sort of attention that close reading or particular type of visual analysis asks.

00:32:19 Speaker 2

Alongside some of the important I think, political, legal, social questions that a critical social scientist would think of, and I’ve always understood myself to be kind of trying to do both, or trying to see one in dialogue with the other. They used to be like these old kind of like literature in society.

00:32:38 Speaker 2

Or, you know, and. And those were, you know, no one uses those terms anymore, but I’d say I.

00:32:43 Speaker 2

Still lug those around this kind of.

00:32:44 Speaker 1

Probably in sociology they do, because we’re such old farts. Maybe it’s just where I am at the moment.

00:32:50 Speaker 1

But.

00:32:53 Speaker 1

No, I love it. And apologies if I misgendered Judith Butler because I know.

00:32:57 Speaker 2

It’s funny. I mean, it’s funny you say that because, Judith, I think started using they them pronouns a couple years ago, but even their way of talking about it.

00:33:03

John.

00:33:05 Speaker 2

Wasn’t ohh I am non binary and use these.

00:33:08 Speaker 1

Right.

00:33:10 Speaker 2

Their way of.

00:33:11 Speaker 2

Saying it’s like I’m currently playing with these pronouns now and so yeah.

00:33:14 Speaker 1

Yeah. Which makes sense because I think their theory is all about how.

00:33:18 Speaker 1

You know, sort of hard categories are kind of pointless and useless and that it’s, you know, it’s in the IT again, it’s in that murky areas, there’s all kinds of murky, cloudy, you know or what you were saying at the very beginning about, you know, like the the leaf moving across the screen.

00:33:38 Speaker 1

Or like small fog or whatever that it’s like, that’s kind of life. Is that it?

00:33:43 Speaker 1

These moments of, just like it’s never clear cut. Everything is always kind of not what we intended to be and not not categorizable in a certain sense.

00:33:55 Speaker 2

And I’d say, like Judith, there’s a philosopher, you know, interested in interpolation and Althusser, or familiar with Martin Buber’s I and Thou or Émile Benveniste, these questions of pronouns have a rich history that our our a sight to think and not only think with, but actually they’re part of. You know categories like that inform how we live our lives and so.

00:34:20 Speaker 1

Yeah. So you know, we’re talking. I wanna. I wanna move on to cause I I love talking to you about this because you refer to Butler as Judith, which I’ve it’s like. But it, you know, I was thinking about it too, because when I was.

00:34:35 Speaker 1

Like, I always get annoyed at students when they refer to, you know, like Max favorite like, well, what? Max said. I’m like, come on, like, show some respect. And yet, if it’s our friend, if it’s someone that we work like it, it’s like I can’t not call you Mike. Like I said to you before, I was like Doctor Michael Allen. Like, it’s just too weird and so.

00:34:55 Speaker 1

I want I wanted to talk to you just a little bit because I was. I was telling you before that like one of the many reasons I wanted to have you on this.

00:35:01 Speaker 1

This is because I love you and I think you’re amazing and brilliant and think in ways that blow my mind, but also because I’m always using you as like a name dropping person. I can brag about and be like, Oh yeah, I have a friend whose supervisor is Judith Butler. And so I want people to know I’m not a liar. I just wondered, like, I’m interested in sort of thinking about, like, what was it like?

00:35:21 Speaker 1

Like what is it like to have had and you know also like Saba Mahmood, who you worked with is like, you know, an important anthropologist, like what, like everybody doesn’t get to work with the like, how do you get to have had Judith Butler as your supervisor? What was that like like?

00:35:39 Speaker 1

Why did you like, did you go up to her and ask her like, hey, would you be my supervisor? Like, how does, like tell me? Tell me about that experience, if you don’t mind.

00:35:48 Speaker 2

Yeah, I mean, part of me is tempted, I mean, and I I would say first and foremost that there are people we think with.

00:35:56 Speaker 2

And that’s important and.

00:35:59 Speaker 2

Friends, colleagues, you often learn, or at least I learned as much from my colleagues, my fellow graduate students.

00:36:10 Speaker 2

As I ever did up the ladder, but one of the things I really.

00:36:14 Speaker 2

Respect and admire deeply about good advisors.

00:36:19 Speaker 2

Is that they?

00:36:20 Speaker 2

Create communities of students around them, and insofar as they’re creating a community of students, they’re creating a culture for thinking, learning, and engaging critically and generatively that others don’t. And I I would say.

00:36:25

And just.

00:36:38 Speaker 2

And she was well, very dear to my heart. She was they were largely the reason I went to Berkeley.

00:36:44 Speaker 2

And.

00:36:45 Speaker 2

And they, you know, in their they created a writing group among those of us who were writing our dissertations with them.

00:36:54 Speaker 2

Saba Mahmood and incredibly, someone very very dear to my heart as well and Saba worked very closely with students and created generations of students who are still remain some of my dearest friends. And so someone passed away a few years ago.

00:37:13 Speaker 2

And what she left behind.

00:37:17 Speaker 2

Is people who are very, very dear to my heart and not just intellectually, but emotionally, who essentially make the work we do as academics worthwhile. And so there’s the the Judith Butler institutional celebrity. There’s the Saba Mahmoud institutional celebrity.

00:37:38 Speaker 2

Why I cared to go to Berkeley was not the celebrity, but the community. I knew that existed at that university, and that continues. I always say the best university is not University of Ottawa, not University of Oregon.

00:37:55 Speaker 2

Best University is the friends we have and that that’s you. Curate your friendships and wherever you wind up teaching, those are the people you learn from. And so.

00:38:04 Speaker 2

My indebtedness to Judith Butler or Saba Mahmood or Karl Britto or Tony Kaes, or Trinh Minh-ha, or Kaja Silverman, a long, Mary Ann Doane, like a long set of people I worked with who’ve really informed my thinking, my indebtedness to them is really comes from a community that they make.

00:38:24 Speaker 2

Possible. And that’s like reading citations. It’s footnotes. Sorry to go on for so long, but there’s so many ways where that to me is what a university is. It’s that.

00:38:25 Speaker 1

That is.

00:38:36 Speaker 2

That connection among scholars who are drawn to think together, who may not ever meet in person but who learn from one another, and that to me, is what higher education is above and beyond a managerial complex. That is, you know, revenue generating are based on what? That’s the stuff.

00:38:56 Speaker 1

I.

00:38:56 Speaker 2

Ignore it.

00:38:57 Speaker 1

Yeah, I feel like I’m a little emotional today, but I’m like I.

00:39:00 Speaker 1

Want to cry?

00:39:01 Speaker 1

Like like like it? Like Amen, you know, say a prayer for that. And I think, like, but what I love about you, Ottawa or my colleagues and the students that I get to work with and that I get to learn from and who are doing things outside.

00:39:17 Speaker 1

Really push me because.

00:39:19 Speaker 1

It’s like they don’t have someone that could work with that. Like I get all like all the students who do anything genderly and sociology. So there’s things like, you know, well, like, transgender, like, what is what is gender or Tyler Escott, who is on another episode and talks about, like sex and sex workers. And it’s like, that is totally outside my sphere. But I’ve learned so much from them.

00:39:39 Speaker 1

And and I think it’s part of what I love about you so much. Is that ever since I’ve known you, it’s like you have this.

00:39:46 Speaker 1

Respect for everyone around you that it it is like you do these fancy things and yet it’s it it like that’s not why you’re doing it like you’re just genuinely curious about, like, learning and understanding others and like just so respectful of the.

00:40:06 Speaker 1

Of of the potential and capacity of every person you come in contact with to, like, offer an interesting idea to the world and it’s like just such a beautiful person.

00:40:17 Speaker 2

Well, I mean thing is you never know when these little.

00:40:20 Speaker 2

Miracles happen, which is like would I have known when I went to work at that feminist organization outside Washington, Washington, DC, that I would wind up in an office alongside two people who would become lifelong friends and from whom I learned? And yet.

00:40:38 Speaker 2

You know, were.

00:40:39 Speaker 2

We the best interns? Maybe not like from a from like the instrumental fordist logic of were you productive? No. Did I learn more from you and Devin that summer than anyone did? The conversations we have absolutely impact decisions I made about what I would do.

00:40:57 Speaker 2

In the future.

00:40:58 Speaker 2

Absolutely.

00:40:59 Speaker 2

OK. And so I mean that stuff where like the you know there there were famous people working in our realm when we were there, but to me, you’re the most famous person I encountered there. Like that was just because it’s true. Like, that was the inspiration for me.

00:41:07 Speaker 1

Yeah.

00:41:13 Speaker 1

Devon has a Wikipedia page. I’ll just say Devon has a Wikipedia page. I do not.

00:41:15 Speaker 2

OK, well.

00:41:18

OK.

00:41:19 Speaker 2

We’ll call it a tie. You and Devon, where? You know, but it’s at the level of inspiration that I I gained from that. And I say that not.

00:41:27 Speaker 2

You know, nearly out of a bit, it’s.

00:41:29 Speaker 2

Just I feel.

00:41:29 Speaker 2

Like, those are the often underappreciated phenomenon that we have all through our education that don’t get the spotlight, that don’t necessarily get the framing. And yet for every one of us.

00:41:43 Speaker 2

That’s that’s. That’s what matters. Like. That’s why we watch why we do the jobs we do.

00:41:45 Speaker 1

Yeah.

00:41:48 Speaker 1

Yeah. And I think it’s like partly why I’m feeling emotional about it too. It’s cause it’s like I can’t get so like tired and like frustrated about.

00:41:49 Speaker 2

Rather than yeah.

00:41:59 Speaker 1

My institution, and you know, we’re like in a bargaining here because we’re unionized, which is great and it’s like and it’s tricky because it’s like I’m very privileged person and like there’s a lot of privilege that comes with being a professor. But there’s a lot of work and there’s a lot of, like, you know, it’s like this. They want to make our classes bigger and it’s.

00:42:20 Speaker 1

Like they would if we had rooms that had enough seats and it didn’t like.

00:42:25 Speaker 1

Pose a problem for fire code and but it it it’s like this pressure to just like bring people in and bring them out and like I can get really like I keep saying to myself like I give a ton of feedback to my students and I’m always like I’ve got to do less. I’ve got to do less and it’s kind of ****** ** now that like you’re talking cuz it’s like why?

00:42:46 Speaker 1

Like why do I need to do less and like I meet with my students as a group which did begin as like an efficiency thing like it began as like I’m getting more and more students and I can’t meet with you like one-on-one all the time because I just don’t.

00:43:00 Speaker 1

Have that time, but it really.

00:43:03 Speaker 1

Has become a space of like. No, you’re like a first year master student. Here’s a third year PhD student, and you can all come together and you can help each other and start thinking in these ways that they hadn’t thought about before and collaborating. And like, that’s what it’s about and you can’t get that. Like, I have a lot of respect for a lot of like.

00:43:24 Speaker 1

A lot of part time instructors that work at the university and that’s important, but it’s like this idea that you can just have. It’s like as long as you have enough part time. Instructors fill the classes.

00:43:33 Speaker 1

And then minimize the number of regular professors there like that. That’s, you know, this cost cutting thing because boards of governors that are overseeing and making these decisions, they’re all, you know, working for banks and whatever. And the people who actually understand academia don’t, you know, they have no voting rights on the, like, executive of the board or like.

00:43:52 Speaker 1

There’s all of this bureaucracy and it’s like it feels so often, like so pointless and fruitless, and it’s like, why am I even bothering? And I think it’s also partly why I started this podcast, because it’s.

00:44:03 Speaker 1

Like I like I. This is the most favorite thing I’ve ever done in academia. I think is this podcast because I just get to have, like, I get to talk to my colleagues and here, what is it that you’re doing? Because we it’s like we don’t even get time to do that. It’s like we’re just so constantly having to, like, crank things out or do our own thing. And it’s like to take these.

00:44:23 Speaker 1

Moments to be like I am excited about what it is that you’re saying and I value what you’re doing and I think it’s interesting and I want to hear more about it. It’s just like it is so fun. It’s like there’s not enough fun.

00:44:38 Speaker 1

In in these settings, so I just.

00:44:41 Speaker 2

Well, as as I always say, like technical education, which seems to be the drive not just in the US, but in Canada, OK and Australia that this sort of what they call on our campus career legibility turns every class into an apprenticeship for a job that may or may not exist in the future.

00:45:02 Speaker 2

And if there isn’t that Direct Line between what 1 learns in a classroom and what 1 ends up doing for employment, then the class is a waste of time and resources. That anxiety comes out of the sense that there are fewer jobs.

00:45:17 Speaker 2

Or whatever the types of jobs that exist are, not necessarily you.

00:45:23 Speaker 2

Know.

00:45:24 Speaker 2

Making use of an undergraduate education.

00:45:28 Speaker 1

Yeah.

00:45:28 Speaker 2

But technical education begets technocratic thinkers, and I think many, and I blame our generation of academics, are just little entrepreneurial.

00:45:39 Speaker 2

Machines who function and thrive in a technical unit, technocratic university. But what’s fallen by the wayside is the North Star of education. Like what does it mean to be educated?

00:45:53 Speaker 2

What is the place of education socially?

00:45:56

Yes.

00:45:57 Speaker 2

And I think those questions like why large courses are an intrinsic good and that’s taken as a given when in fact that model might be at odds with.

00:46:10 Speaker 2

The types of inspiration and connections and friendships we described as so integral to what we do and what we find value in. I just you know, I I I find myself.

00:46:24 Speaker 2

Not to say constantly driving for recentering, the educational mission over and above some of the technocratic noise, in part because I don’t always agree with the.

00:46:38 Speaker 2

The lack of principle that seems to be driving a lot of the decisions for universities in the 21st century, and I think our generation and yes, I’ll blame our generation, has lost sight of what a university can be.

00:46:50 Speaker 2

The world that spawned Santa Cruz and what used to be new College in Florida or, you know, Antioch College or all of those experiments in higher Ed that were amazing incubators for experimental thinking and creativity and were valued as such, now seem almost laughable. Not I’m not on my part, but it just seems that like where, where are we now?

00:47:09

Yeah.

00:47:13 Speaker 2

What’s become of that sort of vision for what education can be?

00:47:17 Speaker 1

Yeah, I I I totally agree. And there’s, I mean it there is as you said, it’s like I, I I don’t even know if I would say that it’s like a value less, it’s like the value has is just it’s the value is not education, the value is not like thinking the value is not like creation.

00:47:37 Speaker 1

The value is efficiency and and that is just not a value that I you know, there are moments like, as I said, I began my groups.

00:47:46 Speaker 1

With efficiency, because I needed it.

00:47:49 Speaker 1

But that’s not like my personal driving force. And I think that that is so often well and also this just they were, I was laughing with like in horror, I forget who I was talking about it with, but there was some former Provost or Dean at my school and they were they were an economist. And they said if you’re a good teacher.

00:48:10 Speaker 1

It doesn’t matter if your class has 20 students or 100 students.

00:48:16 Speaker 1

Great.

00:48:16 Speaker 2

Yeah, you know what’s inefficient? A classroom.

00:48:17 Speaker 1

There’s.

00:48:21 Speaker 2

And you know what’s inefficient? A classroom that teaches you to think critically.

00:48:27 Speaker 2

And in a sense, like if we wanted efficiency in the world, then we will have like essentially create a YouTube channel with some software algorithm that duolingo’s and accompanying file for that YouTube channel and you’ll have active and engaged learning. So then.

00:48:46 Speaker 2

If what we do in a classroom could be recorded and put on YouTube, then why would a student come to class? So whether you’re teaching 100 students or 20 students?

00:48:57 Speaker 2

Make the in personis of that class worthwhile. And I know when you teach or when I teach, like the miracle isn’t me standing in front of a group of people blabbering away. It’s what we do in class. And so I I feel like our students value that often. Our parents can value that. And yet the idiom of our age for.

00:49:17 Speaker 2

Governance and higher Ed seems to have lost sight of those unintended.

00:49:25 Speaker 2

Surprises that happen in an inefficient classroom.

00:49:29 Speaker 1

Totally, totally. And like one thing that I like, we were taught like I was a department chair last year and a I was just like, like the one of the topics of conversation throughout, like, how we’re going to do with that. Everyone’s stressed. And there were some people who were like, I hate AI. I’m not like, I’ve even stopped Googling for, like, birthday present ideas because I need to use my mind.

00:49:50 Speaker 1

And I’m like, well.

00:49:52 Speaker 1

I think I’m still going to use Google and I I actually really like AI. I’ve started using it for variously or like even for you know, my for the podcast or like the website where I’ll be like I can ask questions like what are the most common questions people have about methodology? Like, there’s all these uses, but to me the thing that makes it so that I’m not worried about AI is that.

00:50:12 Speaker 1

AI is a replicator like it is a. It is a, it is. It’s not. It’s like a.

00:50:18 Speaker 1

I would say it’s not even a. It’s not a synthesizer of information, even though we sort of describe it. But it is like it. It pulls out what has already been said. What AI cannot do, and maybe someday it will. But so far what it cannot do is create new ideas. And so to me it’s kind of like a I was saying this to somebody else, like a calculator where it’s like it can do like figure out, OK, what’s everything that’s.

00:50:37 Speaker 1

Been written on this topic.

00:50:38 Speaker 1

But the kind of magic that happens when we are thinking of new ideas and it’s, you know, or or when we’re in a classroom, like my favorite thing is when.

00:50:49 Speaker 1

And talk about, like this unsettling, dead settling places. When I ask a question and I have no idea what the answer is. And it’s like I have this series of questions I’ve been asking, and I suddenly I’m like, at the precipice where I’m like, holy ****, I have no ******* idea where this is going. But it feels like something good is here. And then someone says it and then I’m like, yes.

00:51:10 Speaker 1

Get to some idea that it’s like you can’t AI yourself there like you can’t.

00:51:16 Speaker 1

Like that just doesn’t happen and the like. Human capacity for thinking in new and like to trouble our ideas.

00:51:25 Speaker 2

But it’s interesting because as you talk about AI and your response to.

00:51:28 Speaker 2

It it I I love.

00:51:31 Speaker 2

What AI can make us value and the story you just told is a crescendo towards excitement.

00:51:39 Speaker 2

Yeah, it doesn’t laugh. It doesn’t get excited. It doesn’t get triggered. It doesn’t get angry, doesn’t get upset. So many of the things that.

00:51:49 Speaker 2

Professors complain about in classrooms.

00:51:51 Speaker 2

If you find yourself as a professor being like, oh, my students get so angry or they don’t take this seriously. Those are the moments to value because that’s what AI is not capable to do. So it’s the sort of relationship between learning and feeling that a classroom produces in a like that sort of social chemistry.

00:52:02 Speaker 1

Wait.

00:52:12 Speaker 2

That exists in A room.

00:52:14 Speaker 2

That, to me is the values like. It’s the feeling part. It’s what is it that moves you to think a certain thought?

00:52:20 Speaker 1

Oh yeah, totally.

00:52:21 Speaker 2

We know what moves AI to think thoughts, and it’s it’s a coding problem.

00:52:25 Speaker 2

Yeah.

00:52:26 Speaker 2

But students in a classroom, faculty in a classroom, we’re not coding problems because we’re triggered. We’re angry. We we’re cynical. We’re occasionally funny, intentionally or unintentionally like these. These are all the things that actually to me, are that’s a sort of more holistic or 360°.

00:52:46 Speaker 2

Learning experience and that’s not to disparage AI, it’s but it is to.

00:52:51 Speaker 2

Say this is what this AI moment helps me value about what it is to be in a classroom.

00:52:57 Speaker 1

Yeah, I love that. And also part of what I wanted like in my notes or whatever I was thinking about my question about about Butler and then had to do with Hannah Arendt, who wrote, like one of my favorite books ever is the human condition. And but what, like, it also speaks to.

00:53:17 Speaker 1

What we’re talking about now, where it’s like she wrote that right after Sputnik went into the air. And so she was trying to sort of ask this question of, well, what are we doing? Like, what is like because it’s so easy for us to allow.

00:53:30 Speaker 1

Technology and leaders of technology to become the sort of.

00:53:36 Speaker 1

Like instead of having politicians or like democracy be what’s leading us, that it becomes that, you know Bill Gates or Elon Musk suddenly become the people who are leading us in a particular direction. And she suggests that this, especially because it was to like.

00:53:55 Speaker 1

That into outer space that it is this idea of we’re going to be able to transcend our human condition if we can. If we can find just the right technology and that and that we are constantly trying to get away from our humanness. And I I just love what you’re talking about. Because what you’re saying is like, no, we need to like.

00:54:15 Speaker 1

Get into our humanness like we need to dig into it, and it is so uncomfortable. And it could be so.

00:54:20 Speaker 1

Messy, and it can be just, you know, uncomfortable. But that is what, like that is what’s real. And that’s what’s enduring. And and also like related to the Butler stuff as she talks about sort of art and the ways in which.

00:54:40 Speaker 1

So much of the sort of human condition is this desire for immortality and this desire to like never die, and that it’s, you know, art is a is a non use object that will persist for a very long time. And so if we ourselves also to get back to.

00:54:58 Speaker 1

Your.

00:54:59 Speaker 1

Stuff on film it’s like.

00:55:01 Speaker 1

That this idea that we can capture a moment in time and then it’s like it’ll never die. And I think what’s so troubling to us about, like the Lumière brothers films like those, those mistakes is this like desire of us to like create this enduring.

00:55:21 Speaker 1

Perfection of like a world in which we can all someday like feel amazing and happy, and everything will be OK when it’s like no life is.

00:55:32 Speaker 1

Tough, you know.

00:55:34 Speaker 1

And I think it’s like that embracing of the mistakes, the mess the the ellipses is really where like we are going to keep our jobs and not get fired for.

00:55:48 Speaker 2

Robots have always sort of marveled in the science fiction narratives.

00:55:54 Speaker 2

Of robots taking over the world, it was to produce the possibility of endless leisure.

00:56:00 Speaker 1

Right. Are you there?

00:56:00 Speaker 2

Is the worst part of the jobs that would be done by robots.

00:56:04

Yeah.

00:56:07 Speaker 1

I feel like I get to.

00:56:08 Speaker 1

I I am often seeking that in my life.

00:56:13 Speaker 2

Well, your next two performance reviews can be both written on AI and probably reviewed by AI.

00:56:18

Yeah.

00:56:20 Speaker 1

Right. Well, that’s like here they’ve started apparently in like the the what we call the faculty or like the College of Science. They for all of the lab reports, they’re all being graded by AI. And I’m kind of like, is that such a bad thing? Like, for really basic stuff like, is it so bad that then?

00:56:36 Speaker 1

And like the profs can and TA’s can be freed to do you know, think about things that are a little more interesting than this, like, really basic ideas.

00:56:47 Speaker 2

Well, when it comes to writing, I mean, I love that if AI is grading writing, then suddenly I do think we’re going to live in a moment where mistakes in writing or a trace of human experimentation which make grammatical error and all this these truly valuable.

00:56:47

I don’t know.

00:57:08 Speaker 2

Objects like so if you’re buying a sweater that’s been produced by a machine, it looks.

00:57:12 Speaker 2

The list, but when you know your grandfather has shown you as has knitted you a sweater and there’s an imperfection, that’s the trace of an incredible sweater. And so too with writing. Like own your errors, imperfections shine.

00:57:28 Speaker 1

I I I am all.

00:57:28 Speaker 2

Through.

00:57:30 Speaker 2

And thinker be creative, but don’t be perfect.

00:57:33 Speaker 1

That’s right, that’s.

00:57:33 Speaker 2

Because the machine does it better than you.

00:57:35 Speaker 1

That’s right. That’s actually I went to some like Norwegian museum once a long time ago. And then?

00:57:41 Speaker 1

And they’re beautiful, like fine knitted things. And but they always intentionally one mistake because, Oh my God is perfect. Like, that’s so nice. That’s that explains all of my typos. And like my book that was like copy edited 100 times. God, no, no, no. I just want to make sure we all.

00:57:58 Speaker 1

Know that God is.

00:57:59 Speaker 2

You’re just a millimeter away from perfection.

00:58:01 Speaker 1

From.

00:58:05 Speaker 2

And always have been.

00:58:07 Speaker 1

Oh my God. You’re too kind too kind. Anything else that like we should talk about that I’m missing.

00:58:15 Speaker 2

There’s journal stuff.

00:58:16 Speaker 2

That I have like a little and.

00:58:20 Speaker 1

Yeah, I would love to hear because it’s like, yeah, what, like, just practical device? What do you want to say? Yeah.

00:58:21 Speaker 2

OK.

00:58:24 Speaker 2

There’s like, OK, I mean there’s.

00:58:29 Speaker 2

A couple of thoughts. 1 is that journals. So with comparative literature we get about 200 submissions per year.

00:58:36 Speaker 1

OK.

00:58:37 Speaker 2

And so.

00:58:39 Speaker 2

That’s a large number, blah blah blah by number means does everything go out for review a fraction of what comes.

00:58:46 Speaker 1

How many things? Sorry, sorry. How many? How many things do you publish? Like, so you get 200 in and.

00:58:47 Speaker 2

In. Yeah, go ahead.

00:58:51 Speaker 1

Like what? How many get pictures?

00:58:51 Speaker 2

So I would say if we have 200 submissions a year, somewhere around 16 submissions actually go on to appear in print.

00:59:00 Speaker 1

Wow. Wow. Yeah, yeah.

00:59:01 Speaker 2

Unfortunately, and I mean, this may be the case in the humanities more than in the social sciences, but they’re just are not. A lot of journals that publish unsolicited.

00:59:12 Speaker 2

Material.

00:59:13 Speaker 2

We try at comparative literature to keep you know.

00:59:13 Speaker 1

Ah.

00:59:16 Speaker 2

We don’t. We do.

00:59:18 Speaker 2

One possibly one special issue per year, sometimes one every other year.

00:59:23 Speaker 2

In part because.

00:59:24 Speaker 2

We do value remaining a venue where scholars can submit their work.

00:59:30 Speaker 1

Interesting. So so by solicited like that you actually are going.

00:59:34 Speaker 1

Like is it that it’s like a special issue or is it that you’re actually going and inviting people?

00:59:41 Speaker 2

It is, it’s it’s special issue would be guests guest edited, but I guess what I was going to say so to be one of those authors.

00:59:48 Speaker 2

Where you submit your work.

00:59:50 Speaker 2

You’ve got a peer reviewed and it comes back. There are seasonal certain things people about the there’s seasons to when most scholars are sending their work in and it tends to be at the end of A at the end of a semester. So we get a whole a large number of submissions in October.

01:00:05 Speaker 1

Yes.

01:00:11 Speaker 2

And we get a large number of submissions in February or March.

01:00:15 Speaker 1

MM.

01:00:16 Speaker 2

So your this is just to say your likelihood of being considered might be higher if you’re not in a list of 30 submissions that have come in that the committee has to look at, but you’re in a list of five.

01:00:33 Speaker 1

Interested. So what are the good months?

01:00:36 Speaker 2

I would say the good months from the point of view an author would be slower months.

01:00:40 Speaker 2

Which would be.

01:00:42 Speaker 2

Like, well, the Canadian systems different. So but April.

01:00:47 Speaker 1

See, that’s when our semester ends. So yeah, I feel like everyone sends out things in, like, OK, Late March. Yeah. Interesting.

01:00:53 Speaker 2

Late March, let’s say late March.

01:00:57 Speaker 2

So the the other thing is.

01:01:00 Speaker 2

November early November can be good, but then you don’t want to interfere with the American Thanksgiving or the winter break so.

01:01:11 Speaker 2

Ohh.

01:01:12 Speaker 2

Late March, early April.

01:01:15 Speaker 2

Late October early November.

01:01:18 Speaker 1

This is so I find this so interesting, like this is very good practical advice for like new researchers, which is like one of the audience and my main audience. But it also I find so fascinating to just say fascinating. I also think it’s so fascinating.

01:01:36 Speaker 1

As like how human back to the conversation about like humanist. It’s like how much things that seem like objective or like fair or like like so many things are just determined by like being human beings. And so it’s like holidays or you know, it’s like with my students. I’m like, don’t e-mail me on a Friday afternoon.

01:01:56 Speaker 1

Because I will be, like turning off my phone and then whatever I get in on the weekend, your emails are gonna be like, way low on the list. So, like, schedule your e-mail to send it to me at Monday at like 10, where I’ve already filtered through my messages. And then I’ll read it and I won’t lose track of.

01:02:12 Speaker 1

It you know, but.

01:02:13 Speaker 2

Right. No, that’s exactly.

01:02:15 Speaker 2

Yeah, the other.

01:02:18 Speaker 2

The other thing I would say too is like titles are incredibly consequential and matter a great deal, and so I would always say as an author, you’re allowed to abstract nouns.

01:02:33 Speaker 2

And two proper names, meaning you want a balance between abstraction and specificity. But if if the Journal, for example, we get a piece on.

01:02:34 Speaker 1

I’m writing this down 2 apps.

01:02:46 Speaker 2

You know, let’s say.

01:02:49 Speaker 2

Genres of alterity, like that title like Ohh interesting.

01:02:51 Speaker 1

Hmm.

01:02:54 Speaker 2

M.

01:02:54 Speaker 2

But then it’s like, I guess, well, another way of saying this work that’s problem oriented and it leads with its questions and its problems.

01:03:03 Speaker 2

Is often more charismatic than a detailed study of a case whose significance is not necessarily known unto itself.

01:03:06

Hmm.

01:03:13 Speaker 1

Yes, I.

01:03:14 Speaker 2

We don’t lead with the case, but lead with the significance.

01:03:17 Speaker 1

Yes, I have like a formula for an introduction that I put on my website doing Social Research dot.

01:03:23 Speaker 1

And like it always, I’m always like you got to start with the hook. Like the hook has to be like, oh, I’ve never thought about this thing. And then it’s like, ohh, here’s this weird context. And then it leads to like, well, research, you know, this is all like one sentence, one sentence, one sentence, like research has shown us this.

01:03:41 Speaker 1

But we still don’t know this.

01:03:43 Speaker 1

And then so this paper of mine is going to try to answer that using X method. Last sentence is and This is why we should give a **** like and. It’s so because even when we’re trying to and actually this is so interesting talking with you too is that like sometimes I’ll have students who like a lot of my students, really love.

01:04:03 Speaker 1

Oh, my God. Why am I blinking on her name? Sarah Ahmed, like we all love Sarah Ahmed. She’s amazing, right? And so I have so many students who try to write like her, and I’m like.

01:04:13 Speaker 1

Sarah Ahmed has like a very clear style and it’s very cool, but it’s like you have to one of Butler’s work. She talks about her use of like, difficult language and she’s like, I like her question. They are like, I like hard questions. I like have like I like working my brain. I like doing that. So shut up about it or whatever.

01:04:33 Speaker 1

And I think like I tend to write in a very like I kind of do the opposite, but I after I read that I was like I so respect that. But no matter what style you’re doing, it’s.

01:04:44 Speaker 1

Like people are gonna, there’s certain conventions that it’s like if you do that, people are going to understand it and then you can go, you know, hog wild with whatever the ideas are within those conventions. There’s, like, I picked up some book by Marshall Mcluhan once at a used book fair. And I can’t what it was called, but it was like, you know, this sort of 1960s.

01:05:04 Speaker 1

Like, really, like, Pomo thing, where it’s like he’s writing in the margins and there’s pictures and it like, made no sense. And I’m like, this is fun.

01:05:13 Speaker 1

But like, what the **** is he doing? You know? So if your point is to say ohh look, a book has certain conventions and I’m gonna push them then like. Yeah. But if you have a point beyond that, I always think following these conventions will make it easier to have your transformative, interesting ideas. And people will be much more.

01:05:34 Speaker 1

Quick to get on board and then eventually you can become Mike Allen or Judith Butler or Sarah Ahmed and then you can write whatever you want cause people will trust that you know what you’re talking about you.

01:05:47 Speaker 2

Yeah, I mean I would add to what you’re saying. One third thing, which is if you do get a rejection from a journal, don’t overthink.

01:05:54 Speaker 1

Yeah.

01:05:55 Speaker 2

It.

01:05:56 Speaker 2

Truly, I mean, and that’s where I, as someone who I fear that, you know, I’ve been editor of comparative literature now for seven years. Ish.

01:06:05 Speaker 1

Oh wow.

01:06:06 Speaker 2

So my name. I’m like the person who rejects everything. You know that. That’s. I’m. I’m most often sending rejection letters and I feel it it it actually it.

01:06:16 Speaker 2

I’m in that position myself, you know. I know what it’s like. It sucks and it really. And then you’re often like what? What about this piece didn’t resonate with the journal, blah blah blah.

01:06:26 Speaker 2