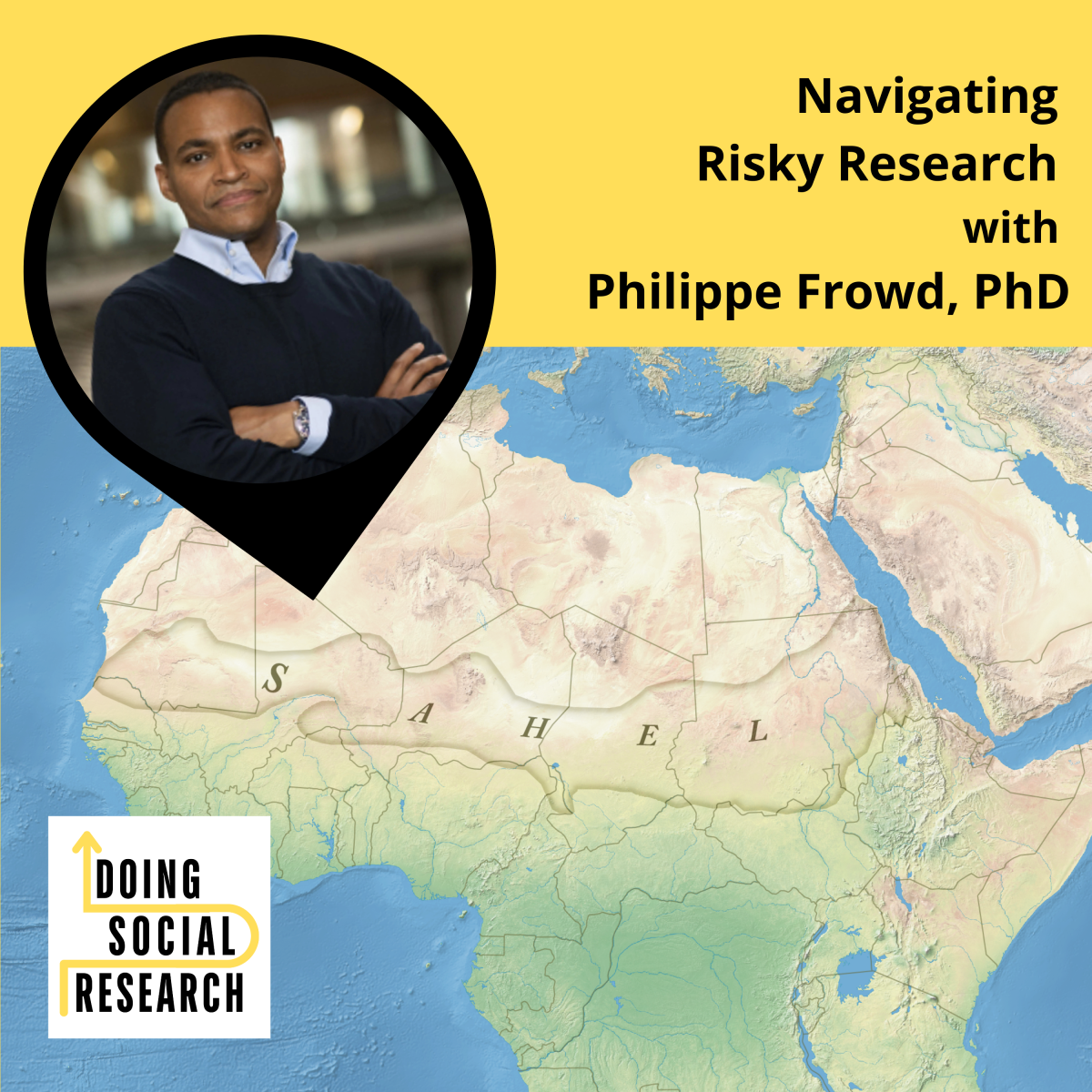

In this episode, Phyllis speaks with Professor Philippe Frowd, PhD, about his research on the politics of security and migration governance, particularly in the Sahel region of West Africa. Philippe shares his experiences accessing hard-to-reach participants, such as border guards and policymakers, using networks and unexpected encounters to build trust. They discuss the value of meaningful qualitative interviews for providing essential context often missed in quantitative analyses within global health and security studies. Their conversation also touches on ethical dilemmas in qualitative research, such as avoiding extractivism, maintaining professional boundaries, and empowering participants in the research process, as well as the complexities of supervising students while critiquing neo-colonial systems of power.

GUEST BIO

Philippe M. Frowd, is an associate professor in Political Studies at the University of Ottawa. He holds a PhD in Political Science from McMaster University (2015), and an MA (2010) and a bachelor’s degree in Social Science (2008) from the University of Ottawa. Philippe’s research focuses on borders, migration, and security constructions and interventions in the Sahel region of West Africa. His fieldwork in countries like Senegal, Mauritania, and Niger examines the intersection of global and local security efforts, using qualitative ethnographic methods to explore their social construction and discourse of transnational governance and border security.

He has authored numerous articles and two books, including Security at the Borders of Transnational Practices and Technologies in West Africa, published with Cambridge University Press in 2018, and Research Methods in Critical Security Studies (2nd edition), co-edited with Mark B. Salter & Can E. Mutlu published with Routledge in 2023, and is an editor for the Security Dialogue Journal.

Organisation Mentioned

The International Fund for Agricultural Developments

Copenhagen School of Security Studies

International Organisation for Migration.

Useful terms

Regrets Folder and Outtakes – Documents used to store sections of writing cut or not used from one paper use in a potential future project. Can be therapeutic and possibly useful.

Boarder Security Technological Strategies Mentioned

Names Mentioned

Works Cited

Lamarque. H. Philippe.M. Frowd. 2018. Security at the Boarders: Transnational Practices and Technologies in West Africa. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Mark.B. Salter, Can.E.Mutlu. 2023. Research Methods in Critical Security Studies: An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Parmar, Inderjeet. 2012. Foundations of the American Century: The Ford, Carnegie, and Rockefeller Foundations in the Rise of American Power. New York: Columbia University Press.

Rippey, Phyllis L.F. 2021. Breastfeeding and the Pursuit of Happiness. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press

Transcript

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Hello, and welcome to doing social research, where I talk with some of my favorite people who do Social Research to dig into the cool projects they’re working on, along with the struggles and successes they’ve had in their careers.

My goal is to help demystify research for students, inspire other researchers and provide a platform for all the brilliant work that folks doing research in the humanities and social sciences.

I’m your host, Phyllis Rippey a Professor of Sociology at the University of Ottawa and creator of the website doingsocialresearch.com.

But then, we are not here to talk about me we’re here to talk with the lovely and fascinating Philippe.M.frowd.

Philippe is an associate professor in the department of Political Studies at the University of Ottawa where he researches the Politics of Borders, Migration and Security intervention, all of which are things I know almost nothing about but I am extremely excited to learn more.

Philippe holds a PhD from McMaster University after getting an MA and Bachelors of social sciences from the most excellent University of Ottawa.

In the in the less than 10 years since graduating, he’s managed to published 2 books an impressive number of articles in a good many commentaries interviews for both scholarly in public audiences.

What is particularly impressive about all this to me at least is the context within which he has conducted much of this research, the Sahel.

And for those listeners who don’t know what or where that is I didn’t either and I actually Googled it. So, according to the NGO The International Fund for Agricultural Development.

So, I’m quoting them just dealing with words, The Sahel meaning the shore in Arabic is a vast area crossing 6000 kilometers from east to West Africa it covers many geographic and agro ecological systems 12 countries it is home to 400 million people.

The political region of The Sahel as defined by the United Nations strategy covers 10 countries, Senegal, Gambia, Mauritania, Guinea, Mali, Burkina Faso Niger, Chad, Cameroon and Nigeria

the region faces many challenges including political instability which is weak in the livelihoods of households, threatens the sovereignty instability estates and undermines social peace.

And for full disclosure, I’ll just say part of why I invite you is that a mutual friend of ours mentioned a comment that you made about a rather tense interaction that we were witness to among some academics

where you said something along the lines to her that you’ve had experiences basing border guards with machine guns in the Sahel and they were less stressful than that which also maybe think of that little adage

variously referred to any presenter or political scientist Warren Sneed among others and academics politics are so vicious because the stakes are so small. I digress.

I very excited to learn more about the research we’ve been doing both about politics large and small so welcome to my podcast.

Philippe Frowd: Thanks for having me and thanks so much for the kind introduction.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Mhmn. Well, to start just you know I’m building my brand. So what research are you doing these days?.

Philipe Frowd: Uh, These days, I’m doing I’m always doing a couple of different little things and I always try and keep you know much in the same way that I cook I kind of research in the same way and try policies

Professor Phyllis Rippey: But you, you go there right like you do you do ethnographic fieldwork there.

Philippe Frowd: Yes

Professor Phyllis Rippey: So can you tell me a little bit about that like where have you been like what did what do you do?

Philippe Frowd: I’m lucky to maintain kind of social and professional networks across the region and Some there was one of the countries that I kind of expanded my work to in the mid twenty 10s

and so I’ve been very lucky to maintain kind of professional relationships there that enable me to go back for a week or two and to do pretty extensive interviewing so I’m I’m less I put less emphasis on sort of ethnography side

but it is still certainly qualitative field work that enables me to have a point of contact with the sort of quote, unquote field in a way that I would not feel comfortable writing certain things without having that point of contact.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah, I think that’s so interesting as someone who’s trained to do quantitative research

I think because I have social anxiety as I’ve done more qualitative research over the years and just engaged with more qualitative researchers is just that idea of relationships

that and how important that is in any kind of project but it seems like what from what you’re saying that that’s especially essential for this for the work that you do.

Philippe Frowd: Yes.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Like how did you how did you develop relationships with, I mean you’re talking to like border guards right and like polices.

Philippe Frowd: Yeah.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: And like, these are not people that are in my imagination, they don’t seem like they’re like looking to make new friends.

Philippe Frowd: Exactly, exactly. Uh, very much actively avoiding that in many cases and I remember being very very discouraged uh when I was doing my PhD proposal um,

and emailing you know regional experts in various places including in Mauritania and hearing back from one person in particular who said you are going to have absolutely no luck with what you’re doing

no DG is going to want to speak to you also you don’t speak the local Arabic dialect, Hassania, Yeah, so you don’t speak any of that so you’re going to have even more trouble.

So, but, I was kind of already committed to going and I thought I’m going to try and go anyway and it was quite difficult at first you know the first few weeks are quite hard

but in the end you managed to leverage kind of personal relationships sometimes an element of luck as well it gets in there and so in the end actually that was some of my most successful field work

in terms of getting access to people so those are the range of this range of ways you can you can do that so for accessing kind of EU people right EU policymakers people in European embassies

often there on LinkedIn or something like that sometimes they’re on there but that’s not their main network so when they get a message on there they read it cause it’s rare so that was something that I found very useful is doing a sort of LinkedIn search for peoples keywords in peoples jobs.

Um, another thing is looking out for workshops and training events that are happening right so trying to get access so seeing if there was you know

like I’ll give you the example one was in Mauritania and there was a two week counterterrorism training that was happening there and that was put on by someone that was kind of within my extended network

and so I was able to sort of negotiate access to sort of sit in on this training.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: That’s so good. Laughs.

Philipe Frowd: And then you get the list of people who are there, and you think oh there’s a lot of people here actually that I’ve been that I would never have found

otherwise no phone book nothing like that.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: That’s so smart! And also, like that like a two-week training right after a couple of days it’s like you are buddies,

you know it’s like cause you’re having your lunch with everybody and it’s like and you just are chatting all the time, that is so brilliant.

Philipe Frowd: Yeah, and they think who the hell is this guy?! You know like,..

Professor Phyllis Rippey: But by the end they are like, ‘this is my pal Phil!

Philippe Frowd: Yeah yeah exactly and so we were you know we’d sit down at tea breaks or something like that and I’d have my,

my notebook out and I just ask questions and I think also having some geographical familiarity cultural contextual familiarity, so I have I have family origins in West Africa too.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Okay.

Philipe Frowd: So there’s certain there’s certain intangible things that one kind of understands of how that relates

and how to behave with people especially is a much younger person at that time too there’s also sort of seniority question which is beyond the sort of seniority of ranks in the security sector

it’s also kind of you’re a young kid who’s just showing up in this place and trying to ask people who are much older than you very direct and blunt questions

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yes.

Philipe Frowd: As if you were an equal and so that in the end was not really an issue so much but knowing how to navigate some of the little cues

I found has been has been helpful in general doing research in the Sahel. So there’s access in all sorts of different ways sometimes it’s through you know connections

like so I was lucky to meet a Mauritanian student in Senegal who also gave me just one phone number of somebody who knew and I just found that person over and over and over again and then…

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Laughs.

Philipe Frowd: And then when they relented, we had an interview and then that was in the part of the national security directorate in Mauritania and so was able to just hang out on his couch

for a while in his office as people were coming in and out and so again that was when I did not go with participant observation on my mind

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Mhm.

Philipe Frowd: And then I quickly realized that because the people I was speaking with were often quite busy and often at the centre of a lot of activity quite literally

in their in their physical environment that in fact the participant observation became a strategy that imposed itself because you could learn a lot from overhearing certain conversations

even if they were not in the language they understood 1 little word or one little reference,

you think oh, they must be speaking about this thing but you know you see things on people’s desks.

You know you see like little post it notes and letter head from a particular organization you think

oh I didn’t know you had worked with them or something like that so that becomes the basis of a question that then can be actually quite useful.

Phillipe Frowd: Um, and in the end you know when you’re writing some of the publications that come out of these projects you may have 37 interviews but there’s going to be 5 or 6 that you really,

really use where the person said a lot of interesting stuff or had some turns of phrase that really help, help you illustrate something and sometimes those are the interviews that take place in those you know the sort of hour and a half at this person’s desk.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yes. I appreciate you saying that. I’m saying trying so hard with this podcast not to make about me but I work as I said I was trained as a quantitative researcher

and I’ve learned quantitative researcher and I’ve learned qualitative through working like colleagues and and I teach research methods and so and I have done a number of qualitative projects

but I have I didn’t have like a professor who like marked my work or something you know and so…

There are I have exact times where exactly that and I always thought Oh my doing it wrong because I’m not like using all of the participants information but it’s like but these people were the so they had so many good things to say so I’m always word I’m like am i cherry picking

but it’s but I hear what you’re saying it’s like it’s actually some people have thought about the thing more or more informed so of course you’d use their information.

Philipe Frowd: And sometimes it depends on their position right sometimes you, you get an opportunity to speak to someone who’s very senior and in fact that’s less interesting

because they don’t have as much experience on the ground as some of the more low level people.

Um, so you know what one person I spoke to in Niger was you know I was in a taxi going somewhere else and this was a police officer who flagged down the taxi

and of course the taxi driver stopped picked up the police officer who was clearly going he was going to the police headquarters in fact where I was going to

and I saw that when he he was carrying a big bag and he put it into the trunk of the taxi but the bag was still open and he had a bunch of pasta in the bag that had Arabic labeling.

So I thought okay, I know a little bit about how subsidized food from Algeria and Libya gets makes its way across this to help I was thinking this guy may have been in the north of Niger

recently if he went to stock up on pasta and so I asked him just a question about northern Niger like yeah I’ve been working on border management stuff like I’ve been trained by the EU

and the Spanish police on like border management and all this stuff so we kind of nerded out in the taxi.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: LaughsPhilipe Frowd: Right? But it’s like these little cues and like finding them

is quite it’s luck but you have to engineer your luck I wanted to come back to something you said about systematicity, and like being trained in a quantitative which I’m sort of terrified.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Laughs.

Philipe Frowd:...at the idea of quantitative research because I wouldn’t know where to begin and

sometimes I wonder doing a lot of interviews whether you can sort of systematize sometimes your research results

and I have never been one to use very fancy coding strategies. I do a lot of my stuff in Microsoft Word in fact most of my work happens

in like 3 or 4 applications none of which are en Vivo or anything like that you know.

So it’s relatively unsophisticated analysis but I’ve done quite extensive coding and analysis of my interviews but it is the question of systematic city is always one that I posed myself which is like have

I spoken to everybody I could have I spoke to three of these people but there’s 500 of them my just getting a biased sample and so trying to determine when if I reach saturation in terms of my research

when I got the answers not just that I want but that are out there and it’s always been you’re always in doubt when you’ve reached that point because there’s no big survey.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Nah, Yeah, they did a workshop that was on how to do Bayesian statistics

I don’t really I don’t know how to do it at all but I was I was curious it’s just like a different way of thinking that it was it’s right nobody don’t even know about it

but he just kept saying he kept saying objectivity through transparency

And I just loved that idea even though is quantitative but I think it’s true and I say it like I teach a lot of research methods courses and I just say

it’s like nothing we do is ever like whatever truth there may or may not be in the world like we’re never going to capture it perfectly

and really you know everything is subjective to some degree or another. I do believe that there are some facts.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: You know like sort of like you know corruption is real, like these things yeah so but I love this idea that it’s like just informing the reader this is

what I did so you know like this is here’s the story of what I did here is the evidence that I collected out now you can make of my analysis what you will.

Philippe Frowd: Mhm.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: But I’m at least telling you what I did.

Philippe Frowd: Yes, it’s like the plausibility of what you’ve said and like the rigor of it and like rigor is not only in terms of the quality of the information

though it is that but it’s also like how we’re using it and are you acknowledging the limitations of some of that information.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Totally, Totally.

Philippe Frowd: Like we and again one of the projects I mentioned at the beginning I’ve been working with two colleagues in Germany on this piece about you know how Sahel states collaborate in the absence of overarching effective overarching security structures

and, you know we had a reviewer asks about civil military relations and like you know we have some of we have some interview data on that not a huge amount

but then we have to we have to use what sort of plausible information in responding in responding to that review and responding to the fact that maybe it’s a question of semantics

how we’ve described what we’re doing so we just need to redescribe things differently in the absence of having very, very detailed field work data to answer the very, very specific question.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah.

Philipe Frowd: Um, So again, it’s about weaving together a narrative that is persuasive but that’s sort of aware of its limitations.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah and I think I mean like I do quantitative because it I mean I was trying it it’s all like sort of a random happenstance of reasons why I ended up doing quantitative

just where I have go to grad school cause it was near my parents and they only did it was like you don’t find this encounter but there were zero qualitative research in the sociology department.

Philippe Frowd: Very empirical sociology

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Totally and kind of old school like but I mean I learned a ton and it was you know that was great but I can figure rotated especially at like

more particularly around like global health kinds of things this insistence on like quantitative data when it can’t tell you anything and it’s like there’s the reason why I started doing qualitative is

because I had questions that can’t be answered with survey data and the stuff that you’re doing anything in particular is like you can’t create a

like randomized experiment to see how does like do goods get traffic from east to West Africa like such is not possible.

Philipe Frowd: Exactly and sometimes it you know this is the question sometimes you know presenting at a conference I’ll get a question about you know migration flows and numbers and the

numbers themselves the way that they’re generated is very very, very unclear but it has tons and tons of limitations that the people who collect them will also acknowledge.

For example in Niger a lot of the information about you know who’s passing through cause the EU considers it a transit country and so is very concerned with like how many people are entering

and exiting a lot of that data is gathered by the international organization for migration which has observers in various towns and cities including at bus stations and so on and they extrapolate from the observations of people

So there is a kind of empirical thing there, there’s some quite in-depth Social Research in away happening but it’s by no means somebody sitting there like a club bouncer with

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah, i was just imagining someone with a clicker. Laughs.

Philippe Frowd: With a clicker, at the border so, using that data then, one has to acknowledge the limits of it and its political usages.

You know the EU will use it to point to the success of its interventions

but I don’t think that as researchers we have a tremendous degree of utility for that data because even when we consider

you know do does a particular border security intervention reduce flows or not, um, everything is over determined

in many ways and if you’re if you’re going in curious about security in the constitution of security

in fact it’s about the political usage of the numbers that’s more interesting than the numbers themselves and another aspect of this work that I’ve done over the last 10-15 years in West Africa has been that an increase in numbers somewhere is often compensated by a drop somewhere else right?

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Mhm.

Philipe Frowd: and so the closure of the western Atlantic route that I had noticed as a PhD student or the relative closure of that is partly what increased in-fact the number of people going

through the Sahara desert through to Libya and so again the numbers game is it’s more game of relative numbers rather than precise calculation and they’re trying to move away from this

desire to precisely calculate social phenomena especially when we consider concerned with questions of meaning which is fundamentally what a lot of critical analysis of security is about.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah, tell me more, I was thinking about like I notice that you know that you identify yourself as like a critical security analyst so how does that,

what does that mean for those who don’t know.

Philippe Frowd: And that’s, I mean that’s a, that’s a huge end useful question because I think critical approaches to security have been in development in some ways

since the early 1980s partly in response to perhaps more rationalist approaches in mainstream international relations which kind of see security as a question of the state the security of the state end of Interstate relations and very much defined by some of the kind of hard facts that you mentioned

Right? like they’re real hard facts how many nuclear weapons does the United states have that’s a countable fact

but it is not the entirity of what security is or means and although there has then obviously lots of emphasis in sort of mainstream security studies on those questions of perception and so on

critical security studies is concerned with kind of security as a strategy of defining meaning and also security as a strategy of governing,

Philippe Frowd: and so one of the kind of key texts is from what gets later called the Copenhagen school of security studies which defines security as a speech act right

this idea that the word security itself has very little kind of innate meaning it is essentially kind of empty container into which meaning is added through the kind of invocation of existential threat.

And so there’s been lots of sets of refinements to that over the years and a lot of other currents inspired by continental philosophy and and many other approaches including actor network

theory and some of the new materialism for example so so now critical approaches to security are in fact very very broad and have a kind of I would say the thing that unites them

is a kind of let’s say non rationalist approach to understanding security.

But beyond that there’s a huge theoretical diversity so I’m one of the editors of security dialogue and in fact we always have this kind of question of well what is the mission of the journal

and like what is the scholarly community of the journal and there are in fact multiple scholarly communities some of which are much more geographically circumscribed

but that are still part of the kind of broad thrust of constructivists slash non rationalist approaches to security studies

but they’re obviously more radical traditions as well in there in terms of how you link thinking and practice for example.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah yeah there was this super fascinating book that I read recently and I cannot remember the name of the author

but it was looking at like major foundations like the Rockefeller foundation the Carnegie foundation and,

and it was discussing the ways which those foundations really developed international relations and the foundation

the Ford foundation that this was a way really of instead of creating a American imperialism through the development of university programs like American University of Cairo or something.

Yes, so is is that sort of the tradition is sort of begin’s very much like to support sort of international leads

and so the way you’re approaching it is to start saying well let’s look at it from other perspectives than just how elites…

Philippe Frowd: Yeah absolutely and so there is the kind of elite reproduction question which is you know generating you recruits for the state department in defence department right or generating better analysis of Foreign Relations and foreign policy.

And then when you look at kind of critical approaches within international relations and security

and elsewhere you see that those have rather different roots but still have these kind of in many cases institutional roots that these are institutions that have also built out of some of these places that were supported by various foundations

right so you know when you look at for example peace of research right so lots of peace Research Institute for example the one in

Oslo are kind of incubators of peace research in the 1970s but also then begin to take in some of the insights of critical security studies overtime

yeah using common institutional foundations to the mainstream and the critique.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah and it’s interesting how these things morph, like even if you know whichever Henry Ford grant

like whatever one of the fords grants it was that started it was like it’s still like academics that are being employed by these places like some will maintain the kind of you know Neo liberal or

whatever other kind of approach whereas others will maybe shifted morph in…

Philipe Frowd: And some of them are quite hands off right I think so in Germany there’s a quite similar sort of phenomenon with like the Volkswagen foundation for example funds a lot of

academic research I recently went to addition gentleman that was funded by the Carlsberg foundation for example but again they were quite hands off there was no free beer but yes but it

was definitely…

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Oh right.

Philippe Frowd; the project was funded by them and I don’t know if I don’t think they have a

particular interest in West African politics but that was just one of the research projects that they were funding and so it’s quite interested to see sort of like disinterested funders I don’t know if

that’s just a year seems to be sort of in the tradition of some of these American foundations too so so one would expect more interference in the research but I haven’t seen that in many cases

Professor Phyllis Rippey; That’s so interesting I don’t think I want to go back to that you mentioned earlier but I think I’m hearing it alot throughout as well is this notion of positionality

and this idea of where you locate yourself and you know so partly like you were saying that you had family from this hell but also even you know being in elite speed not in elite like all of these

you know, and the idea that we were talking about about how do we identify the truth or like

whether or not we’ve done a good enough job at, in our qualitative research I think also means reflecting on our positionality I wondered if you could talk a little bit about that

Philippe Frowd: Yeah absolutely so I mean position I would be in all sorts of terms including in class like I’m a second generation PhD but first to be a social science PhD

so I have I have no claim to well I’m not an insider but I have no claims to be sort of an outsider to scholarly work so I mean that that’s also I

I wondered to what degree that sort of shapes what we want to do like how you end up in I could be in the 1st place I haven’t really gotten answer to that myself I didn’t think I wanted to go into even when I was in my masters.

I think it was something that was in the early it’s something that was definitely a later professional ambition once I realized that I enjoyed research and the work of research but then yeah positionality in terms of origin is also interesting

because for me part of the part of the attraction of studying West Africa it was not actually my first intuition

actually I kind of got into critical security studies through an interest in surveillance and sort of surveillance politics and what it means for observation and practices of data collection to have a

political meaning uh, and that’s how I got into the kind of question of how that applies at international borders and I’ve long been interested and I think lots of us perhaps in the sort of

African diaspora are interested in the question of why can some people move and other people cannot, right?

So why is it that people that are in our family have no real prospect of even traveling to Europe or going anywhere else and you quickly realize then the dynamics of race class citizenship and so on that are that are operating there and so that probably part of where the interest in borders comes from and the borders in discussion of who can move and who cannot and under what logics,

Philippe Frowd: Um, positionality in terms of doing field work is that’s the kind of sharp end of the stick I found and I found that working in West Africa and being of kind of mixed heritage you

kind of benefit twice in some ways because you benefit from proximity to whiteness sometimes and having done research with white colleagues you you begin to see ah oK they have certain

advantages maybe have some of those advantages too alongside them but then also a benefit of having cultural familiarity and ability to culturale integrate in a way that also yields that also

has benefits for research and it’s interesting and sometimes difficult not to try and mobilize yourself to extract research data.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Oo tell me more.

Philippe Frowd: Right there’s always this thing that you have that you sort of wonder like am I applying my cultural knowledge or cultural capital in the pursuit of extracting research data that I

then leave with an amazing very very conscious of trying not to do that I don’t have a full systematic understanding of how but I think one of the ways is not trying not to get too close or

personally close with interloops in terms of my research sometimes keeping things reasonably professional showing some degree of understanding and so on but not necessarily trying to

develop deep personal bonds I think that’s one way perhaps of not feeling like I’m extracting data I think that’s what it is.

Professor Phyllis Rippey; mhm. yeah and thats sort of like you know taking peoples time and then like doing what with that input like there’s no reciprocity in certain sense that’s the thing it’s

yeah and I mean I think I also I was talking with another another podcast guest just about sort of the sort of ethical or moral responsibility we feel to publishing our research even if like I my

project I’m working on now that’s taking me forever it’s like I refused to just drop it because you know these people took time to talk to me would you say you sort of I mean I think I mean

professional boundaries like as you just said is a way to avoid the extractivism that can occur like other things you thought about?

Philippe Frowd; Yeah I’m thinking about you carry on right the even you know you you gonna say extracted but you’ve got certain data and the project maybe is not clear where it’s going but

you have a responsibility to those people and I think yeah maybe responsibility is a good way of thinking about it like I I have tried to be systematic and not always been successful at doing this but to do a short write up after doing field work like a page or two to summarize what I did I this is like

Professor Phyllis Rippey; Thats so good OK I’m interrupting you just to be like Phyllis do this because I am so bad about it OK go ahead sorry.

Philippe Frowd: And it’s so because often field work ends with a thump you get on the plane and then you get home and then there’s just craziness like I get home and it’s just like back-to-back

to my kids and my brain goes into a whole different mode and I sort of quickly forget what I you know 24 hours earlier I was in Niger or something like that.

So I find that sometimes an writing it as soon as possible maybe even on the plane writing 2 pages of like what did I do what did I what did I see in a sort of policy oriented way and just

sharing that back with the people that I spoke to because that gives them an idea of oh what else is going on who else has been saying similar things to me and sometimes they discover in fact though they were not the only person to say or think a particular thing

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Oh my God i love that, I’ve never done that i’m so bad and it’s so

Phillippe Frowd: I got this idea from a colleague in the netherlands and she says like she does field work and you know it helps to make sense of it right so just write a two page are that you keep

for yourself but also that that shows that you’re i mean it’s a way of showing that you’re serious

a way of feeding something back when you can’t you don’t want to send a whole interview transcript to someone it’s less useful.

Professor Phyllis Rippey; Yeah it totally well I love it too ’cause actually another another podcast guest is actually a former student of mine Chloe Kim Kim rivers in the broadcaster rose

if it was in her thesis defence but she was sort of 1 to one of the arguments she was making for

why ’cause she does take some sort of phenomenological approach which is totally foreign to me who she first started but one of the things about it was you know.

It’s not about finding facts it’s not about like uncovering the truth but about finding meaning and for each of the participants in one of the things like which was so like it was like revelatory for me

it was this idea that one of her goals was to just to help her participants like speak and also like that they would have fun with it and also like enjoy the process and so…

Philippe Frowd: Yeah, Thats something that we don’t even think about in our research and certainly it’s not what we’re trained to do in like in our research and frankly that sounds like something that would be so good right but like where we’re just sitting here we’re generating ideas together yes think of the interview is that type of interaction.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah exactly so it’s sort of again gets away from this extractivism other words I’m just taking something but it’s like and I had heard like for a long time like I have

a colleague from Acadia Zelda Abraham said she’s to be a lot about how to be a qualitative

researcher and she often would talk about important ’cause we worked on like the ethics research Ethics Committee together

and that she was saying like it is not an inherent good to have anonymized data she’s like there are times where she’s doing you know where you’re doing research where the person wants a

voice they want to be heard and so to automatically assume anonymity is the more ethical choice denies people the chance to take credit for what it that they said.

Philippe Frowd: They dont wanna be aggregated into this big pile into database right yeah exactly but…

Professor Phyllis Rippey; Exactly, exatctly, but it depends, you know.

Philippe Frowd; I mean I think that’s it to you one has to be quite comfortable to propose that

too give you an example I have only just recently started recording interviews and actually having audio

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Wow

Philippe Frowd: That I then transcribed for the longest time I still got all these notebooks in my office now it was all handwritten notes during interviews that were interspersed with journal

like observations so again you know like oh what’s the letterhead on the person’s desk what is the little cues and clues that one finds and so

those are all sort of a jumble of notes that I would type up every day and in fact it’s a that partly was a question of courage I lacked the courage to ask people who are high up in the security sector hey can I just record everything you’re going to say

Professor Phyllis Rippey; yeah but its also like this is the security sector like I can imagine there a little apprehensive about letting you record them and actually I remember I had a colleague at Acadia who did research on Kenya

he looked at like the Anglican church I was in her Boeing but he always said

’cause it was again around these questions of Ethics Committee that he refused to have them sign a consent form because they were

like we do not trust you and this was just about like their feelings about the Anglican church this wasn’t like national security…

Philippe Frowd; And in African in context especially like people don’t want to just sign random stuff

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah and so he would usually say at the end like would you like after the interview was gonna be like could you like would you be OK to sign this or you and I

think ethics says like that was 15 years ago and I think people more and more realize that like other forms of consent or acceptable

but he like it was the first time like that one 2007 that I really thought about sort of you know there’s rules you have to do the rules

Philippe Frowd: yeah yeah

Professor Phyllis Rippey: and people really were like, I mean like Phyllis get a grip like there’s also reality here

Philippe Frowd: Yeah I mean but the rules envision the participant as as mostly week this is often the I mean I’ve been on the I was on the ethics board for awhile here I wouldn’t say that it’s systematic but we typically prioritize the safety

and well-being of participants because you want research to ideally mitigate risks that people are going through that are above and beyond what would be in their everyday life the question

then becomes if you’re interviewing elites healthcare do you need to be of them or how how much do you need to protect them and so I realized overtime that I was over protecting people who are perfectly capable of telling me when they want to go off the record or not

Professor Phyllis Rippey;Oh

Philippe Frowd: I quickly sort of realized that in fact you know you talk to people who are in counterterrorism and so on they know exactly when they need to tell you don’t write this down

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Right

Philippe Frowd: But you don’t need to be so worried about protecting them they are in positions of power and they can tell you then they know what they can and cannot say yeah

Professor Phyllis Rippey; yeah there’s a kind of hubris in up like among us academics where it’s like we assume that like we like infantilizing of our participants

Philippe Frowd; yeah yeah and it’s about you know being conscious of like who is who is empowered in this particular context right and it’s not always clear and we will always have to negotiate

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yes its nota always the researcher

Philippe Frowd: Exactly exactly

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Wow this is also interesting working I mean part of this has to do with trust

Philippe Frowd; Mhm

Professor Phyllis Rippey: And like I mean you’ve talked about a lot of the ways but I’m also wondering like did you ever have sort of people cousin I guess ’cause you’re talking to security officers but was there ever any concern that you had like nefarious reasons for being there that like did anyone ever question if like are you actually part of Cisis or the CIA or anything like that like

Philipe Frowd: Yes that has been that was that that happened during my PhD ones actually and I was in Mauritania and I was I think I had got a ride again you know personal and professional kind of overlap so I had got a ride back from I think it was a law enforcement

context and one of the people who had dropped me off was kind of a mid ranking guy and for some reason we were sitting in the car for a few minutes and he asked me questions about what I was doing he said you know like everyone here thinks you’re a spy.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Laughs.

Philippe Frowd: Like we all think that you’re a spy but he was kind of not particularly worried about it right but I said no no trust me I’m just my card says PhD student that’s literally all I am

I’m like I couldn’t be a spy if I wanted to and I don’t know if that is swaged anybody but it didn’t cut off my access or anything like that

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah

Philippe Frowd: but you quickly find that news news about you travels when you’re studying some of this stuff and so people might be apprehensive but often if you go through proper channels

you regain trust or not regain but you you enter with more trust so sending letter of request for authorization to speak to XY and Z people once you get add authorization people are kind of

cool with it right you know and people will happily help you sort of do a snowball or approach as well and so I found that help me in Senegal where I was able to get the authorization of the of

the chief of the national police to speak to a certain number of people and so once that was there everybody below was like well the boss said we can speak to you

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Right

Philippe Frowd: So this is totally fine and will say will talk about whatever we want and part of the trust question is also demonstrating expertise is also showing like I understand this this this

and I understand that this is sometimes frustrating for you guys or this particular project didn’t seem to workout what was that about and you show that you kind of aware of what’s going on

then it’s much more of a conversation among people who both know what they’re talking about rather than Oh dear please tell me what’s going on because I’m just a student I don’t know anything.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Right

Philippe Frowd: it becomes much more I know stuff you know stuff let’s exchange and that’s more fun sometimes for them

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Again and that goes to the like we’re not just extracting data but it’s it’s a relationship it’s a partnership for this our conversation

Philippe Frowd: yeah, exactly, exactly and so those are often the most fun interviews because then those people are interested in you too

and they actually want to give you more time you know and that’s that’s across all sorts of different contexts in which I’ve in which I’ve done research including in the EU.

For example again these are people who are highly sought after, there’s a whole industry of migration research in the EU that’s often funded by the EU but there’s tons and tons of grad

students who are emailing people at the EU Commission saying hey can I talk to you about externalization of European borders in Africa.

So I’m sure when I e-mail I’m like the 100th person that’s asking for interview so I often wonder and assume, you know sometimes these interviews go to like an hour and then you ask hey

could I speak to someone else and when they say yes you think huh OK did this go particularly well that you trust me to go and speak to someone else? So you wonder you don’t know

but you sort of think OK maybe because this went well and we were both talking about stuff that we’re knowledgeable about

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Right

Philippe Frowd: That it wasn’t just like a student project not to be disparaging

Professor Phylliys; right right yeah and do you ever find like I have this concern ’cause I feel like I had an interview in Jakarta with someone from The Who in my project and my work is all about breastfeeding and it’s very much more politicized than you would realize and so but I’m very critical of The Who in my work and I think part of like the woman was so lovely and so like open she’s like oh like

Philippe Frowd : And she knew of your critiques

Professor Phyllis Rippey: I think so like I wasn’t writing it published a lot but I mean and I’ve always presented myself as like sort of middle of the road it’s like where I’m trying to ask questions and think about like sort of challenge assumptions that we make about breastfeeding so it’s I’m never trying to say like don’t do it or don’t support it like and I’m very supportive of like

I’m very I should say I’m attuned to the ways in which breastfeeding is not supported but I’m also just very curious about the ways in each breastfeeding promotion is like a tool of state supremacy and neo liberalism and neocolonialism.

Philippe Frowd; And the whole global health apparatus behind it that’s like that’s

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Exactly, my critique but I think I’ve been I mean there’s lots of reasons why I’ve been taking forever to get on this project but I have these reservations where

I’m like it’s almost like I feel bad particular like do you have that like as a critical security studies but you’re talking to the people creating the laws making the pool is like doing all this stuff that you might be careful about

Philippe Frowd: Yeah, very much so yeah you often have a rapport with people and you think this person is super interesting and very dynamic and really cares about what they’re doing but

they are part of a big system that is incurred but what they’re doing they sincerely are trying to do their best in this particular work they’re trying to solve problems and faced with the way the

problem has been framed for them they’re solving it in the best possible way but in the end it’s like it’s maybe the framing of the problem that’s wrong.

But often they don’t have much to do about that you know you look at things like the European border regime in this hell is responsible for the deaths of so many people and there are tons of

people who are part of the European border regime who are working as diplomats who are working as all sorts of jobs and who they themselves are not culpable

and who are doing interesting work and who in many ways are people sometimes even from humanitarian backgrounds who are trying to make things easier and better and so it’s individuals

and systems one has to have this sort of separation even though you’re interviewing the individual to get a sense of how that system is working

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah interesting too to like remind us of like it’s not like Mr. burns from The Simpsons is like signing all these things it’s like or if you like him though around yeah

and yeah yeah I’m sure but it is like you know like there are there are bad people but like so often you know it’s like the road to hell is paved with good intentions especially in..

Philippe Frowd: Yes that’s my favourite

Professor Phyllis Rippey: I think in development I can imagine you know like in places where there’s like savior complexes of people in the West it’s like I’m going to do this

and then it’s just like you just pardon my French but you just **** it all up yeah like you know some people may be intentional other people they just

Philippe Frowd: Yep and you know like I think of colleagues a few colleagues in Europe who worked on things like migration information campaigns right like this well intended stuff

which is you know putting up billboards in places like Gambia saying hey have you tried becoming a tailor in Gambia instead of trying to go to Italy and maybe drowning in the Mediterranean.

So you can understand the logic behind things which is we’re trying to save lives by putting together these campaigns to get people to to favor sort of local economic opportunities

and so on but it’s also tremendously paternalistic and also part of the kind of bigger system of migration governance and so yeah I have a few colleagues who studied that stuff and I often think of that example as the quintessential good intentions as part of systems that are actually

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah, yeah, very good just looking at the time I guess I’m going to skip like a bunch of things here because I don’t want to take up all your day

and I really I really want like because like especially with the work that you have done like what you’ve described sounds a really hard like really challenging maybe potentially dangerous.

and I’m just wondering like do you have graduate students who come to work with you or have you or start to work with you like how do you suit like wanting to do this kind of stuff like you know sort of feel like it’s like a parent being like don’t do what I did or do any you know but like how do you how do you navigate that like what yeah what’s that like?

Philippe Frowd; That has been a relatively recent thing so I started my career in the UK and had a few PhD students there but who were not working on African cases though I had one student who’s working on code devore actually who

who went and did a bunch of interviews trying to kind of develop a narrative approach to the conflict there but that was in a post conflict context and so in fact much of our interaction with me in this student was about trying to navigate the universities bureaucracy ‘

cause the university was really worried about the risk factor

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yes.

Philippe Frowd: whereas it’s like well I’m going to the capital of Ivory Coast like it’s not really all that dangerous the war is not kind of going on

and even when it was it was very far away in some ways so that was the extent of my work like

in terms of graduate students going into risky field here I’ve mostly had students who have been working on kind of African cases or stuff that’s close to my area have mostly been doing masters degrees with paper and so it’s been lit review and desk research

I do have one PhD student now from Sudan who’s from Darfur in fact and who is studying

Sudan and decentralization in the post conflict kind of well currently conflict context in Sudan

and so we’ve had preliminary conversations about what’s this going to look like in terms of field work are you going to be able to go or not and so that’s very much unresolved

And I only have my own experience to draw upon and perhaps I think that’s I think gradual supervision honestly is the thing that has the one of the biggest impact in terms of our job and

the biggest impact on another person and it is the piece that we are 0% trained or ready for and it is really just making it up as you go in and you have to do open pray that you had a good supervisor as an example because that’s going to be maybe 60% of your inspiration for how you

do things and if you had a crappy supervisor I don’t know if you then do the opposite or reproduce the same mistakes but I think that’s one area that’s complete blind spot in terms of our training

Professor Phyllis Rippey: That is, i mean, I have never thought about that because like people say oh we have no training in teaching and I’m like well I took a course like there’s workshops

but it’s absolutely true we did not like I there was nothing other than having a supervisor like that is hurt and that’s it yeah and it’s so funny ’cause I often will feel real good like I think the

you know one of the vice president I don’t know but the Provost are somewhat recently produced alike here’s some tips on good supervision for us that I kind of skimmed like a few yes yeah yeah

And it was like OK I think I’m pretty much on the right check but there’s certain things like I hear colleagues that are like they take their students to conferences and they like pay their way and

I’m like I never get grants so I don’t like you know or even like I started after I heard that I was like oh **** I should be encouraging my students to do it themselves yeah yeah yeah

or like I really like I used to meet with my grad students one-on-one ’cause I just had a couple in the beginning but then I started to have 5,6,7 yeah I can’t meet with you that much so I started meeting as a team after another colleague mentioned that she did that it was

Philippe Frowd; OK

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Which I love doing that

Philippe Frowd: I’ve only heard good things about that approach it is so helpful ’cause then they help each other and it’s sort of like sometimes when I there was a period I think it’s like

after that leave where I kind of it was like a bunch of shoes graduated and I was kind of in this flux time and I let it go and then like I wouldn’t have from students for months whereas this is

like OK we have our meeting we set super dictation to exactly it’s like we check in it gives them it’s sort of quasi deadline to work against so I really recommend that you

Philippe Frowd: Do you do it it across level so ma and PhD together OK that’s good yeah yeah yeah I wouldn’t Professor Phyllis Rippey; I have enough ’cause I think I have like 3 PHD’s for one image that just started PhD so OK or PHD’s now and then

Three MA students something like that that’s a good #2 for like a group meeting yes but it does it works out great like they each get you know we just go in a circle whoever wants to talk 1st

and if they need more help I can do one on ones like I just actually met with 1 today who wasn’t able to meet the last one but she also she’s a new ma student

and she’s really trying to she wants to apply for a OGS scholarship so she’s trying to like get her research question firmed up so just needed a lot more sort of like let’s let’s talk this out

Philippe Frowd: And that’s really helpful to have like PhD students giving advice especially for that ’cause it’s like you have to submit an OGS within you know 8 weeks of starting yeah, yeah

and you don’t know what you want to do

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Exactly exactly and she she’s doing I’m so excited but she has a she’s a student ma instruments in gender studies but her bachelors was in engineering Oh well

but I have all these questions about water and breastfeeding and so she like I did all this work

on like water in Bangladesh and so I’m like Oh my God I need you to come here just so I can pick your brain so yeah anyway so she’s all excited it’s

Philippe Frowd: m m thats like really interdisciplinary they often actually coming out of different disciplines actually have some of the most interesting insights right because there’s lots of stuff they don’t take for granted

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Right as things that like she was like we just like taking all these notes it was like all the various toilet styles she was like

her job was to go around in this rural area to help people understand how to ensure that they have clean water and so it was like you know I was like I was drawing pictures I’m like Oh my God this is fascinating

Philippe Frowd: Wow

Professor Phyllis Rippey:Cause you know like breastfeeding and water is like such a big issue in terms of global stuff

Philippe Frowd: but in terms of the thousands and thousands of people like when you look at some of the research around like Nestle and like you know the formula and all this stuff stuff ’cause it’s like the aggregate effects are getting that is

Professor Phyllis Rippey: I know except that what is so fascinating to me is that part of one of the arguments that have started to make that I’m struggling and this again goes to that question of like how do you find your evidence is is trying or I started to see connections between water

privatization and breastfeeding promotion and so and actually this is like I need to talk about around a different podcast or something ’cause I could go on forever but there’s this that the

Nestle boycott was really triggered by this one guy who wrote this paper for this British war on want publication and it was all about like one of the times it was called Nestle kill kills babies.

But it was Oh my God I’m blanking on everything ’cause I’m like I can’t talk about this too much ever he I never ever don’t ever question who is this guy like I just thought it was journalist

but he is whole like expozay about Nestle another formula companies in quote UN quote Africa and all the bad water starts the Nestle boycott and anyway

like last year I was like who is this guy so I start looking around.

I Google him he has been an expert on water privatization like for like 40 years like he was like there was an article in the guardian about him at like having this little chat with the president or CEO of Nestle

being like oh you still gotta work on your formula but this guy is like one of the world’s leading experts on water privatization and why water should be private time this is absolutely not only developing world thing to write

like I mean totally it’s like all over the world but this is like he’s like oh this is the solution to problems of water access in Africa yeah

Philippe Frowd: I mean like having been in the UK before coming here and having had my first kid born in the UK like the a lot of the I mean ultimate water privatization example there as well

and also the health system is very very especially the midwives in the whole system are very very very emphatic about breastfeeding

Professor Phyllis Rippey; right and so yeah so like basically like the argument that I make is that there’s it’s again this unintended like good intentions like I want you know

we want to save babies without realizing that there also are these other interests that it becomes so like I have a chapter in my book where it’s like you can see access to clean pipe water in Indonesia has been on the decline since the law went into effect mandating breastfeeding and yeah so I know I know but it’s like I don’t really I never feel like I’ve like really good evidence like it always feels like it’s his little bits of stuff

Philippe Frowd: But sometimes it’s the intuition that helps others find others who have access to certain data to do it and sometimes like I think a lot of the purpose of our work too is to is to

give is to give others access to that intuition that we had by giving it a name or giving you a little conceptual title and then people take it up yeah and I find that that’s one of the you know one of the only reasons that I keep Google Scholar alerts on.

lIke I’m not particularly concerned with citation count row was concerned with like how people cite something and then you see oh OK that thing that opened up something for someone else

or they use that concept to go and do this thing you think OK you learn from it and then you apply it differently so I think like what you’ve done is not in vain even if you don’t feel you have the data there someone else will see it from

Professor Phyllis; yeah, well im still working on it. Thats why Bangladesh with a bachelors in engineering I’m like with me ’cause I need to understand water better yeah so yeah absolutely

no other one person did use one article for the like exact opposite reason was like see This is why and was like, see breastfeeding is always the best and im like no you missed my point

Philippe Frowd: Still good for the h-index yeah yeah exactly exactly anyway I feel like we’ve

been talking for like an hour and I could go on forever but I don’t want to take all your time especially ’cause I know that you have calls that might be coming to you.

Philippe Frowd: I mean I could go on forever about the grad student thing because honestly I’ve been thinking about this recently sorry I just.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: No no i was about to ask what else do you want to say.

Philippe Frowd; cause im answering a non question but I think like there was a case in the UK or maybe a month ago that was highly mediatised that was in the news of a PhD student from

Oxford or Cambridge, who had made it all the way to their fourth year before the committee rejected the project or something like that.

And so the students sued the university saying like I’ve spent you know 100,000 or whatever it is to go and get my PhD and you told me at the last minute but it’s no good so there was all this

stuff raised where procedurally the student was wrong that the student had appealed and had exhausted all the different ways to appeal and the highest instance I think within the university

but also within this kind of like national standards council or whatever it was said there is no basis you had negative feedback and that’s too bad and so I guess the media route was the final route.

But in the end it raised all this question about what is the duty of supervisors in a committee in terms of giving people feedback a year one or year 2 or year three and not leading them to think that their work is better than it is or being unclear and like that is a whole that got me really thinking about this because we are so unprepared for supervision and it’s so high stakes for people and we often face this decision here at the university

to which is you have a student wants to submit their major research paper and it’s like is it good enough or not if I say it’s not good enough that’s an extra $12,000 you have to spend next week yeah

Professor Phyllis Rippey: And if they are international students, like 42,000 dollars. You know.

Philippe Frowd: Yes and it’s like well it’s up to me with the stroke of a pen I could save you that money or make use have to spend it

for my idea of what I could make rigor is but because we supervised in the four walls of an office it’s not typically something that’s very public and less our students are defending their project or whatever,

so, you don’t really have much peer comparison in the way that you would with publication or with teaching yeah and the only

like i have found it really useful to be on the tenure and promotion committee and social sciences because then i see how many students people supervise how they do it you know how

they frame their supervision style, and even even with that I’m still kind of I still feel really last in terms of what I’m doing.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yeah, I mean I’m sure you’re doing great but it’s it is it worked like how many is definitely a question like that there’s someone

I know who apparently in her entire career should since retired supervised ones doing OK and I’m just yeah I’m like I have so many swear words for yeah but then it’s also like I’ve seen people go with other people

like I’m like you know these people don’t supervise enough students but then it’s like well maybe that’s not their strength you know yes

Phlippe Frowd; yeah give your energy and service to something else right like I thought I had a cat this year I try and do 3 or 4 MAs a year, and I usually tell students pretty comfortably like I’m at my cap your projects interesting

but I can’t be good for you if I’m taking you on but there was one student from the share was like I want to study security and migration in Niger and I was like alright dude I’m going to just for you were going to do this and it’s like

Professor Phyllis Rippey: i know, i know, and I wish there were some way and do it more systematically ’cause I’ll say yes to people where I’m like well you

do gender you do some kind of similar make sure, sure and then look at like 3 people who like suddenly wanted to breast feeding and water Im like, yeah

Philippe Frowd: ’cause that student told the other ones

Professor Phyllis Rippey: I know but it’s so hard to know because I think they’re it like it ’cause I have other college where they have like 12 or 15 students and

I’m like how how are you attentive to them like I’m like I know one column pixel eyes amazing and really good but I’m like I don’t like I don’t know how you do it’s like and I also like I over edit too much like there so.

Philippe Frowd: Yeah yeah yeah but those that’s a really good approach to like because

that’s needed to have those in text comments like really detailed I have one or two colleagues in my department who I’ve worked with on PhD committees or as sort of Co supervision at ma’s or I

see the degree of comments in the paper I’m thinking OK that’s not my exact style but I’m happy that you’re involved in this so that we have complementary styles

Professor Phyllis Rippey: Yes, ues, but it takes so much time, and its like

Philippe Frowd; yeah and I yeah

Professor Phyllis Rippey: I really love and respect just good friend of mine and she’s like item 20 editing I like you know I tell them they can find an editor but it’s like I almost take it too personally but it’s like I take it as a reflection of me or I start like rewriting it like this is not your yeah yeah I’m really excited where it’s really good I’m like

Philippe Frowd; once you get to track changes yeah yeah yeah yeah yeah

Professor Phyllis Rippey; yes, right? I’m trying to start like I’m just going to print it out to old school and I’m just going to hand write it but they were international sorry they were an international student and they couldn’t read my handwriting.

Philippe Frowd; Oh right, yes yes yes, handwriting is a risk now these days.

Professor Phyllis Rippey; Especially cursive, terrable it’s just like I love about doing this podcast is talking to other people and realizing how many things that we’re sort of ringing it’s yes absolutely and we’re winging it in the most expert way possible for absolutely absolutely like it all works like word we’re doing this and it’s like yeah I think in my head baby I’m doing right everyone else do you right when I talk I don’t like.

Philippe Frowd; Exactly exactly the people at the at the big table are just as clueless as we are and sometimes it’s like transferable skills so I found I’ve been doing journal editing for two journals for two different journals one after the other in the last five years.

And you think OK is this just like grading but writ large or in a slightly higher stakes grading and then you realize no it’s not quite that but it’s like what how much of that skill set do I need for for

this and how much of the supervising a PhD student and commenting on a chapter how much of that energy do I bring to the journal editing and in the end the answer is not yes or no it’s kind of

like it depends per person so there are some people who I will send reviewer comments too and a kind of annotated Word document with my comments in it.

And that’s something that I that I just stole basically from another journal that I had dealt with where after the review process the two editors had both put track changes and comments in the

Word document post review for me to deal with it was like a third round of review and I remember thinking that’s really rigorous it’s actually not very highly cited piece for the amount of

work I did but like I thought well that’s so good I’m going to steal that idea but again it’s more

work you have to have that two hours extra that you could have spent writing your own stuff and so does a I suppose a quote UN quote cost to doing that

Professor Phyllis Rippey; yeah yeah so I get so focused when I start then I can sometimes lose track of time and then be kicking myself

so that is why I still haven’t published the Indonesia paper it’s because I am just sacrificing myself to everybody yeah these grad students sure yeah yeah

is there anything else you want to talk about anything else about your research that you want people who are new to doing research to think about or no

Philippe Frowd; I think yeah well maybe for people who not necessary about my research but something I’ve learned that I think can be helpful for people who are starting out a research career is to trust your intuitions to some degree

part of that is even when you’re writing even as an experienced academic when you’re writing there is value in shutting down all the PDFs

and books that you have open and just writing based on your intuitions and then putting references in later not all the time

but there’s value in half an hour of doing that writing a page and then going back and editing it but your intuitions have some value and I’ve realized that from looking back at ideas that I had maybe like 7-8 years ago

and I think oh that would be really really interesting but I can’t find anything about it and no one has really touched this and I feel like it’s really it’s not that it’s too high risk it’s just like maybe it’s just not plausable and then years later

like I should have done that thing actually because now people are doing it or this from another field needs to communicate with this field and just trusting that intuition that you have

Professor Phyllis Rippey; I love that yeah yeah that is such good advice ’cause yeah I have so many regrets like I should just call them like a folder of regrets of like papers I started and then there was one I was so excited was grad student like I sent into a Prof and he just sort of didn’t care about it that much

and I was like this is like like this is a new form of it was about protest suicide it’s like this is like taking dirt kind but like a new idea of suicide like nobody’s ever done this and I was like havent they?

And the prof was like oh I don’t know and he was kind of busy whistling else and then like four years later someone put paper like the top sociology journalism good yeah it was anyway but what are you gonna do that’s the thing

Philippe Frowd; and then you you see someone run with it and go that’s good for you I’m happy you did it but the regrets folder is a very the other thing yeah the regrets folder

and then the material cut from a paper folder yes the little bits that just kind of like little paragraph that you like oh that doesn’t fit in

this I was told to early on never delete anything just cut and put into another document oh takes oh I call it outtakes

Philippe Frowd; Oh dump file which is much less exciting I’m going to start calling it out ’cause I have all these files on my computer called dump file

and are frustrated every time I see them too lazy to go and rename all of them

Professor Phyllis Phyllis; no yeah outtakes but like yeah yeah just but that’s yes I think I’d like a whole chapter of my book with it I was able to look at least starts from like pulling together yeah out takes again

Philippe Frowd; every idea has some value every intuition has some value somewhere but it may not just be for the current project

Professor Phyllis Rippey; I was told that to do that just for the emotional effect because like we don’t want to kill our darlings and so it’s like so you can sort of feel like Oh my God I wrote

these two pages and it heartbreaking especially when you’re like young and just writing and everyone feels like every page feels like more monumental that it was like oh I can’t cut words

but writing is editing like this is what it is and so it’s like OK I gotta put it somewhere so I don’t

like I won’t cry over it it’s like I’m saving it for later but I love how you’re sort of talking about the inverse that it’s not like this is crap yeah save

Philippe Frowd; it it’s like when you make a pie you cut the crust and you take the excess crust you can still use it so I think with the excess dough rather I think and the other thing that I tell students is like thinking is not something that happens only in your brain

like we tend to visualize it that way but like you think about writing sometimes you don’t know what you think so you’ve written on a paper and printed it even

and look at it on the table in front of you and go oh actually I’m going to change that or oh OK that’s actually pretty good

because your brain is not a word processor yeah so you know you gotta write it out to think grad students when they hear that go Oh yeah

Professor Phyllis Rippey: No I love that idea to have like right without looking at the sources but I also have a so often it’s like I’m trying to make an argument and then I’m like I know that I heard this somewhere so then I go and I find this source and I’m like Oh my God it was different than what I remember but this is even better and then I can put that in

Philippe Frowd: Exactly exactly there’s always a bit of …yeah

Professor Phyllis Rippey: This has been amazing thank you so nice getting to like know your work a little bit more and just talk research teaches that like we definitely like I was saying

before we started that you know we don’t get to talk to colleagues that much it doesn’t work but also about these kind of ideas about research more sort of abstractly about like how do we engage in that process yeah yeah yeah and you know

Philippe Frowd: It’s so dependent on who we are what where we are you know that type of thing so yeah it was a pleasure to chat with you and like it feels very self indulgent for me to talk about myself for an hour plus but it was a pleasure to exchange.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: I love it I think that’s also one of the reasons why I want to start doing this podcast is because I realize how much I love talking about and my research and I want to give like I love giving people who I think are cool a chance to just get to like bask in the glory that is decrease urban testing yeah that was

Philippe Frowd: Great Thank You.

Professor Phyllis Rippey: you well if you like this episode please give me give us a five star rating on your favorite podcast platform and we even just a little tiny sentence fragment of what you like about it this will really help us to reach more listeners to make doing Social Research within the reach of everyone bye

End music playing