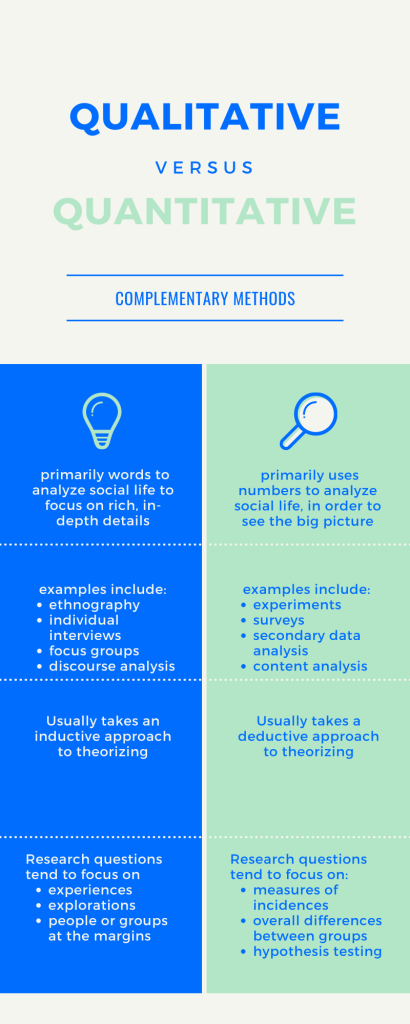

Because of how the research is carried out, qualitative and quantitative research often get separated as though they are two competing research methodologies. I prefer to see them as complementary, where they each serve an important role in the greater goal of uncovering new knowledge about social life. That said, many researchers in practice tend to engage in one or the other methodology, mostly (I think) because they each take a lot of training and maybe some folks figure that doing one thing well is better than dabbling in everything. I, however, am a bit of a dabbler. I was trained in quantitative methods but have used qualitative methods on multiple projects simply because quantitative methods were just not appropriate for my research question.

Both bodies of methods are pretty diverse but a few examples of qualitative would be one-on-one interviews, observational field work, or discourse analysis (the analysis of communicated material), whereas quantitative research often involves statistical analysis of survey or experimental data collected by the researchers themselves or survey data collected by others, such as a government statistical agency like Statistics Canada or the U.S. Census Bureau.

So, what’s the big difference?

At the most basic level, qualitative methods use words more than numbers whereas quantitative methods use numbers more than words to analyze their data. Both methods use words and probably both use numbers to some degree, but the key distinction really is about whether or not one is quantifying, or assigning numbers, what one is studying. Both kinds of methods use data, which means that both are empirical. Some suggest that qualitative research is more interpretive in that this research involves interpreting written or visual text using words, but quantitative research also involves interpreting evidence, but that evidence is in the form of numbers.

Why use numbers instead of words (or vice versa)?

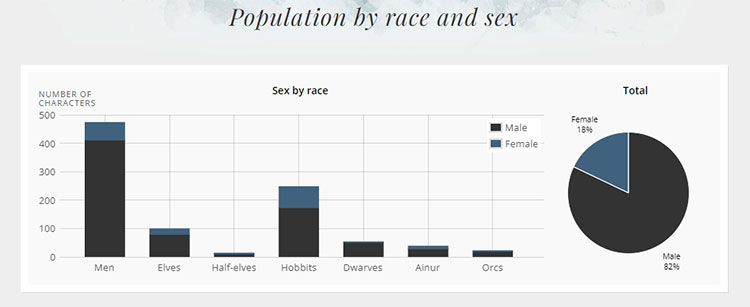

Social scientists are most interested in ideas but sometimes by assigning numbers to these ideas or concepts we can collect, organize, and analyze A LOT more data than we could if we left everything in word form. Think about it this way, is it easier for you to read the Lord of the Rings in one sitting or to read the following graph?

Obviously, that graph is way easier and quicker to read all 1,137 pages of Tolkien’s tome. However, as you might be already thinking, there are some nuances of the book that seem lost in this graph. Where are the lush descriptions of Middle Earth? Where’s Gandalf’s wisdom? Where’s all that Elvish language? Where is teenage hearthrob Sean Astin? (Can you tell I’ve never read the book?) Qualitative research can involve all of that rich description of story and experience. This is especially true for ethnography where part of the job of the researcher is to bring the reader to where the research was carried out. The tradeoff for this rich description, however, is that qualitative research cannot capture as many voices or places. Think about it like a zoom lens on a camera: zoom in and get a few people with lots of details, zoom out and get a big picture but the details are blurrier. For example, look at this photo titled “Green Day Concert Crowd – Put Your Hands Up For Green Day”

From this vantage, our eyes kind of glaze over any one individual and what we focus on is a big crowd of people who seem to mostly be putting their hands up for the band Green Day. If were were to quantify this, or put this into a number, I might say that about 95% of the crowd puts their hands up for Green Day. I mean, I would, wouldn’t you? But what about this guy in the white shirt?

He definitely does NOT put his hands up for Green Day. Why not? I dunno, we’d have to ask him. That would require qualitative research to find him and ask him something like, “What gives friend? Why no hands up for Green Day?” Maybe you’d talk to his friend there, too. Maybe you’d find other people who also didn’t have their hands up and write a whole research project about people who attend concerts of bands for which they would not put their hands up. I’ve definitely seen worse projects.

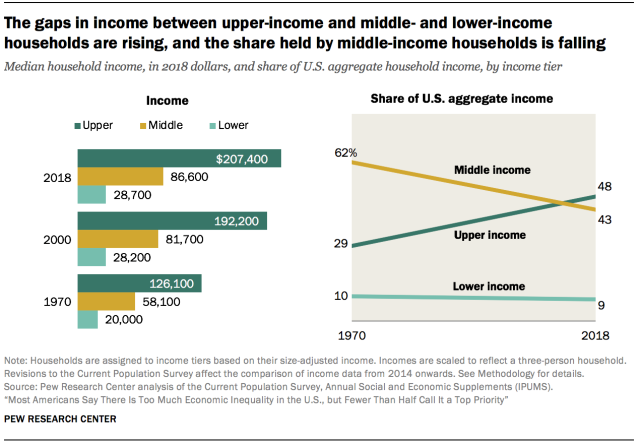

Qualitative sounds great, right? All these stories, so much depth! Why doesn’t everyone do qualitative? Quantitative sounds way too simplistic, no? Well, first of all, there are only so many stories we can capture in any detail. If you talked to 1,000,000 people for a 25 page paper, it’s just not possible to get everyone’s details from each of their stories. And, sometimes, we are more interested in the big picture and are less interested in the details. Maybe Green Day doesn’t care much about the one hater in the white shirt but they want to know that most of their fans have their hands up. Government research studies are often more interested in the whole population of a country than in individual stories because they need to know how the whole economy or particular policies are working overall. Perhaps they have introduced a new social program to address poverty and they need to know just how many people have been able to earn a living wage. Perhaps you want to know how incomes have changed over the past 50 years, like in this graph from a study conducted by the Pew Research Center in the U.S.

While qualitative research could tell us many interesting stories about the people impacted by these changes, those stories would not tell us much about the overall patterns in economic inequality overtime. We would not necessarily be able to tell that incomes have declined for the middle class over the past 50 years, but have rapidly increased for upper class folks. We need quantitative research to give us this bigger picture.

Because qualitative methods involve fewer people and because those people are usually picked for their particular stories, rather than at random, qualitative studies generally are not seen to be particularly accurate at speaking for everyone. There are ways we can try to include diverse stories to adequately reflect the folks we’re interested in, but we can’t really be sure. In contrast, good quantitative research uses randomization to ensure that the participants don’t represent only a particular kind of person. So what we lose in depth, we gain in generalizability.

Differences in Theory

Another difference between these methods is how they use theory. If a research project uses any empirical method but does not engage in theory at all, we would consider those to be empiricist. This is the kind of research we see most often presented by government statistical agencies like Statistics Canada or the U.S. Census Bureau. However, in most social research that gets published in books and journal articles, we want to engage in theory because this is how we get at deeper answers to our research questions. You can check out my post on theory for more about this, but for now, just trust me that theory is important.

Although I can imagine ways in which one could use both qualitative and quantitative methods for either theory development and for theory testing, in general, qualitative methods tend to be better for exploration and the development of theories, whereas quantitative methods tend to be better equipped to test theories. Why? Well, this goes back to the issue of sample size–or how many people we can include in our study.

Because qualitative research studies include fewer stories and the stories not selected at random, the research is less generalizable. This means that any theories that come from the findings may explain only the particular folks in the study. On the other hand, because quantitative research tends to be derived from large random samples, the findings from quantitative research can be said to speak for the whole population. As such, quantitative methods are quite good at testing whether a theory speaks for everyone.

You might think that this makes quantitative “better” because of this ability (and some people, *ahem* those who use quantitative methods *ahem* might say this). However, qualitative methods have a benefit for theorizing that quantitative studies often lack, which is the ability to discover novel insights. Because quantitative studies are drawn from surveys with pre-existing questions or experiments designed to test a theory, finding new ideas within the study is rare. With qualitative, there’s a lot more room for new discoveries that have yet to be found in the pre-existing literature. This is why some see quantitative methods as more conservative, in that they rely more on how things have already been seen or framed, whereas qualitative is often used to amplify the voices of those at the margins whose stories might get blurred in the averages. This doesn’t have to be the case, however, and I personally enjoy finding ways to use quantitative methods to test theories that emerge from qualitative research insights.

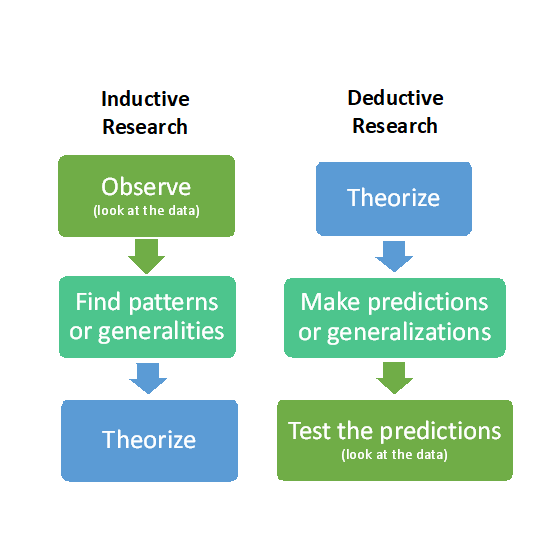

Another way to see the place of theory in these two types of research is that qualitative research tends to be inductive and quantitative research tends to be deductive. Inductive theorizing involves observing a situation, seeing patterns, and then drawing conclusions or explanations (what we call theories). Deductive theorizing works in the opposite direction, where we begin with a theory, make predictions based on that theory, and then test these predictions by looking (observing) our data. Although, this is not always 100% true, in general, qualitative research tends to be inductive because it begins by talking to people or observing and then seeing what themes or patterns emerge from what was observed. Because quantitative can handle large, random samples, but there aren’t a lot of details or room for new ideas, quantitative tends to be deductive by testing hypotheses (predictions) based on theories (drawn from other research).

How do I know which one to use?

Neither type of method is inherently better than the other. The type of method you should use is always going to be determined by your research question; although sometimes this means you have to change your question based on what kind of data is available to you. If you are looking to explore something in general and want to look more in-depth at peoples stories or experiences, qualitative is the method for you. If you are interested in seeing overall trends in the population and want to see if a theory applies in general, then quantitative will be your jam. Some people pick a type of method simply because they enjoy the process of one over the other. Some people love hearing stories from others and observing, others find that stressful and prefer working with numbers behind a computer. I know one quantitatively inclined person who found that everything she tried qualitative research she kept try to get all their answers to be systematic and she struggled to allow all the messiness of people’s stories in. Some qualitatively inclined people find quantifying information too rigid and they miss the insights that can pop up in the messiness of the details. What matters is less which one that you use, than that you use the method that can answer the question you’re interested in. As you can see from the table below, the questions can be quite similar but the qualitative will tend to focus on experiences and explorations whereas quantitative tends to focus on trends, rates, and differences.

| Qualitative Research Questions | Quantitative Research Questions |

| What are the experiences of newcomers to Canada from China? | What are patterns of immigration to Canada from China over the past 20 years? |

| How have working mothers been coping with parenting in the context of COVID-19? | Are there gender differences in the rates of job quitting since 2020? |

| How is life experienced for indigenous people living in remote areas being developed by mining corporations? | Are rates of housing dislocation different for indigenous people living in remote areas being developed by mining corporations compared to other areas? |

Regardless of whether you decide to pursue qualitative or quantitative methods research (or a combination of both!), the most important thing to remember is to be rigorous, systematic, and transparent in the work that you do. No one study is going to answer all of the world’s questions, but with careful research we can continue to better understand this complex and confusing social world that we live in.